PARK WATCH September 2021 |

Executive Director Matt Ruchel and Digital Campaigner Jessie Borrelle explain how the recent announcement is … complicated.

It was an overcast Thursday morning, shaping up to be a very ordinary (COVID-normal) work day – until we received an unexpected call. Our state Environment Minister was about to finally table a response in parliament to the Victorian Environmental Assessment Council’s (VEAC) Central West Investigation.

The contents of their pending response, like the reasons for the 18-month delay in its delivery, were a mystery to us. All the pressure our supporters, staff and community had applied over those long months had so far resulted in nothing but scripted non-answers from the environment department. We didn’t know if they would accept all, some, or none of the expert independent recommendations to create new national parks across 60,000 hectares of native forests and woodlands in the state’s central west.

The quiet months after the Victorian Government officially tabled the VEAC recommendations now seem a different time, a different world. A world before the Black Summer bushfires ravaged our landscapes, consuming habitat, wildlife, property and lives. A world before a ruthless virus took the everyday hostage, with no sign of setting its captives free anytime soon.

To nature-lovers, community, scientists and conservationists, the gravity of these events only reinforced the urgency of protecting swathes of unburnt forests across the west. Having avoided the catastrophic bushfires, they became vital refuges for wildlife, like the Greater Glider and Powerful Owl, that lost substantial populations in the east (see vnpa.org.au/after-the-fires-report). As Victorians turned to green spaces for respite from the sombre notifications of the health crisis, a renewed appreciation of nature unfurled. (See vnpa.org.au/covid_parks_polling).

If, as they say, a week is a long time in politics, the almost two years we waited for a formal decision on such a critical issue seemed like an aeon. To say it was worth the wait would be too much of a simplification of the substance of the government’s response. The best way to describe our reaction might be: hesitantly relieved and pleased – but also disappointed at the contradictory logic embedded in the response.

The big picture:

All in all, the Andrews Government announced it accepts in principle, or accepts in part, 76 of 77 recommendations made in VEAC’S Central West Investigation Final Report.

They are committing to creating the new Wombat-Lerderderg National Park, Mount Buangor National Park and Pyrenees National Park, along with other parks and reserves, including a new regional park at Wellsford near Bendigo. The response was formally tabled in Victorian Parliament on 24 June 2021.

As Victoria confronts alarming rates of ecosystem decline, bushfire recovery and the real-time impacts of climate change, the intention to create new national parks could not come at a better time. Permanent protection is a critical step in managing natural areas for the future.

These new parks will safeguard core habitats in one of our most fragmented landscapes. They’ll be good for both the natural environment and for local economies – as evidenced in our economic report on the myriad values of prospective new parks (see vnpa.org.au/new-central-west-parks-economic-assessment).

The state government’s stated intention to create three of the four recommended national parks for Victoria will eventually add 50,000 hectares into Victoria’s parks estate. While less than VEAC recommended, these additions will grant permanent protection to over 370 rare and threatened plants and animals that depend on (and are integral to) these forests. We’re also pleased to see the inclusion of a new small Wimmera River Heritage Area included at Mount Cole.

The government reassured recreational users that four-wheel driving, trail-bike riding, mountain biking, bushwalking, picnicking and nature observation opportunities will not be impacted, regardless of the fact they were never going to be. They also emphatically pointed to the retention of seasonal, recreational deer hunting in the Wombat–Lerderderg and Pyrenees National Parks, in areas currently permitted, with some restrictions.

While the Andrews Government has committed to their creation, it will still take a long time with multiple steps, and potential setbacks, for these areas to receive the full protections of formal, finalised national parks status.

If we do see these extraordinary forests added to Victoria’s wonderful parks estate, it will be the most significant inclusion in over a decade – a milestone for nature if the obstacle course of political hurdles is overcome.

Can you have your parks and log them too?

The decision has come with strings attached. Tugging a little harder at those strings reveals a convoluted, regressive and mixed set of outcomes, not in line with many of VEAC’s expert recommendations.

An especially disturbing departure from the final recommendations is the gross twisting of VEAC’s implementation timeline. We are alarmed to see that the proposed parks will be logged before being established at some mercurial yet-to-be-specified date. This was not contemplated by VEAC, nor ever discussed during any of the consultation phases.

Continued extensive logging of the forests at Mount Cole (the proposed Mount Buangor National Park) and Pyrenees (the proposed Pyrenees National Park) is deeply worrying. There will be some targeted logging in the Wombat Forest, but this is to be fairly restricted.

The plan to log many of these critical wildlife refuges before turning them into national parks (as late as 2030) doesn’t make any sense. Especially when there is decades of wood supply existing outside of the proposed park areas. More importantly, aren’t we supposed to be phasing out native forest logging according to the Andrews Government’s Victorian Forestry Plan?

It’s disappointing, and frankly egregious, to see the Victorian Labor Government doggedly pursuing native forest logging, a small-minded position directly at odds with community values, a changing climate and the already profound loss of biodiversity across our state.

The creation of three new national parks, hopefully jointly managed by Traditional Owners, and a parcel of new regional parks and conservation areas, is a cause for celebration. But to acknowledge the forests are worthy of protection on one hand while revving up logging machinery on the other is contrary, to say the least.

The details:

For many local conservation groups, this muted triumph has been over 15 years in the making. For others, and the places they have fought so long and hard to protect, it’s an underwhelming outcome.

In what is a glaringly politically-motivated measure, the implementation of our new national parks will be staggered. Some parts of proposed parks, such as Mount Cole and Pyrenees, may not be created until 2030, well after they are unnecessarily logged.

Most regional parks, along with significant areas of proposed national parks, will be available for “commercial thinning” (managing the forest to create thicker logs) and “selective logging” (mostly for commercial firewood and, in one instance, wood chop logs) until native forest logging is phased out in 2030.

Proposed changes to the current Special Protection Zones in the Pyrenees that protect forests from logging are some of the most cynical aspects of the Victorian Government’s response.

Wombat Forest

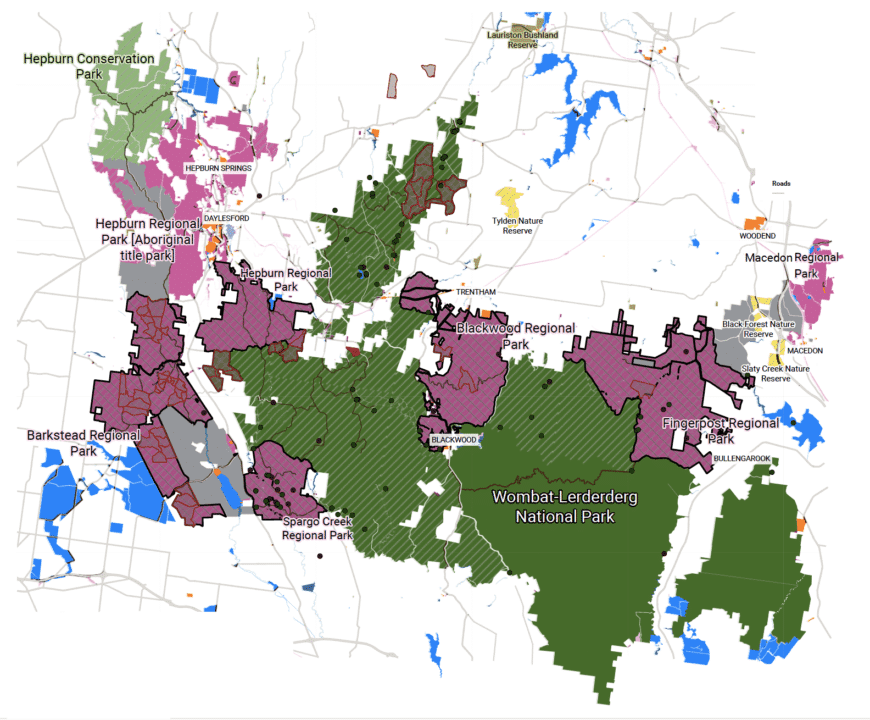

View full version of Wombat Forest map

Overall, the announcement was positive for Wombat Forest – especially so for members of Wombat Forestcare, whose endless dedication to protection for their local forest contributed greatly to the outcome.

They will see the creation the Wombat-Lerderderg National Park protecting 45,000 hectares, which combines the existing Lerderderg State Park with an additional 24,000 hectares.

The size of the national park was reduced by 4855 hectares from the original VEAC recommendations, which will now become Barkstead Regional Park. Additions to Hepburn Regional Park and the creation of Spargo Creek Regional Park, Blackwood Regional Park and Fingerpost Regional Park have been accepted – but will allow continued commercial firewood production and domestic firewood collection.

Worryingly, in the proposed national park, 18 logging coupes have been retained, covering a huge 1206 hectares.

Wellsford Forest

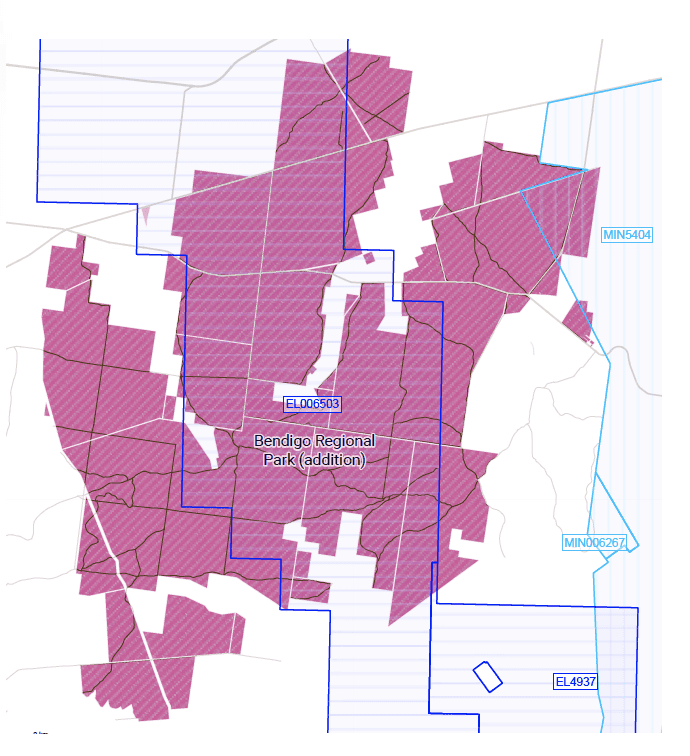

View full version of Wellsford Forest map

The government does not accept the recommendation to expand the existing Greater Bendigo National Park, and instead this area will be added to the existing Bendigo Regional Park. This outcome for Wellsford Forest is of great concern, especially for locals and conservationists who wanted to see the forest safeguarded in the recommended national park.

Failure to give parts of the Wellsford Forest national park status may leave it more vulnerable to mining development, domestic firewood collection, and inappropriate recreational use.

Regional parks are primarily geared to “provide opportunities for informal recreation for large numbers of people associated with the enjoyment of natural or semi-natural surroundings or semi-natural open space”. Environmental protection is a secondary purpose in this context, and instead of ecological objectives given precedence, they need to be “consistent with” recreational activities.

There is some relief to be found in the protections afforded by the new status – primarily an immediate moratorium on commercial logging in the Wellsford Forest – but as regional parks are not formally part of the protected area network, this is somewhat of a lost opportunity.

Wellsford Forest will need to be closely monitored with a proper management plan for the impacts of growing recreational use in the area. Existing regional parks around Bendigo are not subject to joint management, and do not require park management plans like national parks, though Parks Victoria has the power to produce plans for them.

The existing Greater Bendigo National Park is one of six Aboriginal Title parks in central west Victoria, jointly managed by the Dja Dja Wurrung Clans Aboriginal Corporation and Parks Victoria. The national park is governed under a Joint Management Plan for the Dja Dja Wurrung Parks by the Dhelkunya Dja Land Management Board.

The government supports the VEAC recommendation for joint management of central west parks “…in principle, subject to further consultation with Traditional Owner groups, including the three Traditional Owner group entities to whom the State has already made, or committed to make, grants of Aboriginal title under Part 3 of the Traditional Owner Settlement Act 2010 (Vic)” – essentially pushing the joint management arrangements into a separate process.

Mount Cole and Pyrenees Forests

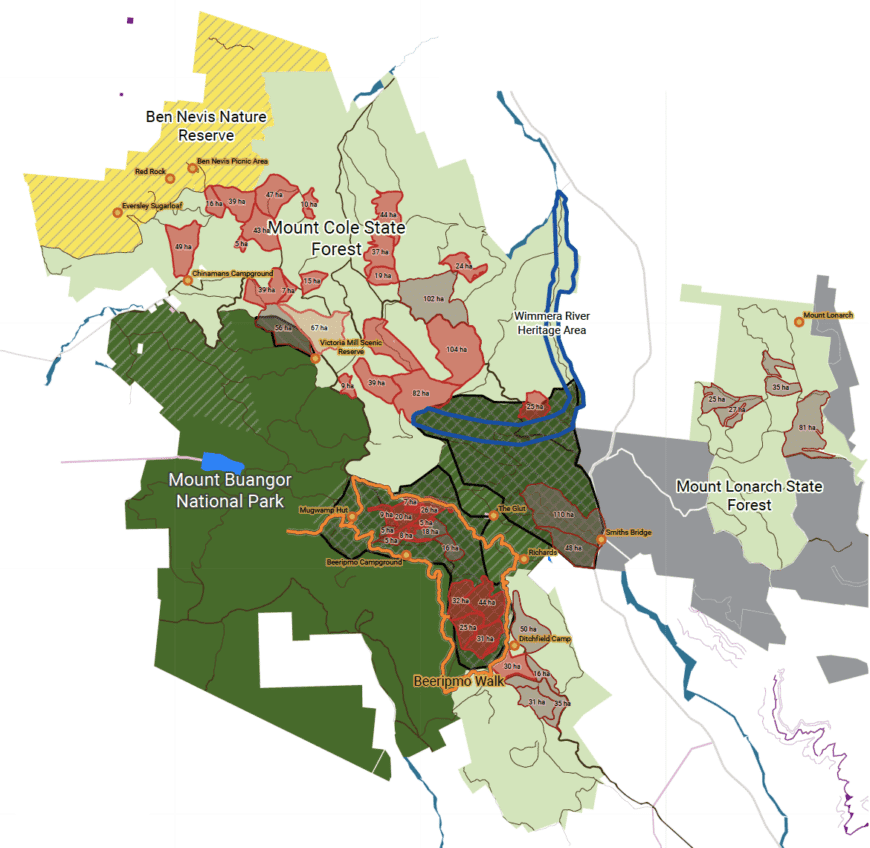

View full version of Mount Cole Forest map

View full version of Pyrenees Forest map

The future of the Mount Cole and Pyrenees forests are the most uncertain and troubling. The creation of the Mount Buangor National Park and Pyrenees National Park will be staged to allow logging in large areas prior to incorporating those areas in the parks, which could take as long as 2030.

Unlike in Wombat, there isn’t a specific list of coupes that remain; instead, we see entire areas open for logging. Logging coupes were increased at Mount Cole in 2017 and again under the new Timber Release Plan issued late 2019 – after the final VEAC report was tabled and the Andrews Government’s Victorian Forestry Plan to phase out native forest logging was released.

This Timber Release Plan increased both the number of logging coupes and the intensity of logging in the proposed national park, notably alongside the Beeripmo Walk – a popular and challenging 20-kilometre track that weaves through the tall forests and cool fern gullies of Mount Cole. Once slated for “selective logging” by VicForests, coupes alongside the walk are now listed for “even stand management” – that is, clearfell logging.

The government’s decision to continue VicForests access to Mount Cole and the Pyrenees for logging operations (including clearfell) is both nonsensical and short-sighted. It’s certain to damage integral habitat in these forests, further threaten plants and animals, and disrupt the enjoyability of the Beeripmo Walk, as well as other camping and walking areas, like the aptly named Endurance Walk in the Pyrenees.

Surely a generous level of cognitive dissonance, or a high degree of political arrogance, is required to recognise the national park values of the area while simultaneously locking in long-term clearfell logging. We’re hugely disappointed by this colossal lack of foresight.

Logging in the west is not as closely scrutinised as it is in the eastern parts of the state. For example, standard pre-logging forest surveys for threatened species carried out in the east don’t occur in the west, leaving citizen scientists – like those in our NatureWatch program – to pick up the slack and do the work government should be doing.

The response from our elected leaders on the Central West Investigation has illuminated the Andrews Government’s position on nature conservation in Victoria, and cast their priorities in the harshest light. Logging first, nature later.

VEAC investigations are supposed to be the formal process for changing land tenure and protecting natural areas. Yet the Andrews Government has placed more weight on its (only four-page) Victorian Forestry Plan, entrenching decade-long logging in areas independently and expertly assessed to be worthy of national park status. Instead of hastening the transition out of native forest logging while progressing nature protection, the government again appears to have been gamed again by logging interests.

Eyes on the prize

What has become clear is that our work here is far from done. We need to be vigilant and do everything possible to protect the value of these important places. The Victorian Government’s commitment is only the first step in the formal creation of these new parks; legislation now needs to be developed, pass both houses of parliament, and the parks formally gazetted.

The implementation timeline is not clear enough, too slow, and could easily never happen in some places. It is unnervingly tethered to the state’s phase-out of native forest logging, a drip-fed approach to squeeze as much timber from these forests and woodlands as possible before new national parks are realised.

The logging of areas proposed for national parks rich in threatened wildlife doesn’t make sense, but it has been done before. In the 1980s, legislation to create the Alpine National Park had clauses that allowed “… once only logging to be carried out …” “… after which areas are to be managed as part of the park”. But the parks creation was legislated up front. While less than ideal, that was a better model than drip-feeding legislation to create parks after logging finishes as is the case for the central west.

The Andrews Government is facing an election next year, another in 2026, and again in 2030. It’s difficult to take such commitments seriously when they may not be governing in 2030. We need to see a clear set of timeframes for the creation of these new parks before this term of government ends in November 2022.

If the Andrews Government is serious about its legacy and the proper protection of these incredible natural places, for current and future generations, it will commit to:

- Legislating all the proposed parks, upfront, in this term of government

- No, or significantly reduced, logging in proposed areas for new national parks

- Greater protection and management for the mighty Ironbark forests of Wellsford

- Election commitments reaffirming the delivery of these parks

- Introduction of pre-logging threatened species surveys in the Western RFA

- Completion of Action Statements for key threatened species

- Funding allocated specifically for park management

- A clear plan to manage domestic firewood supply sustainably across the state

- A speed-up of the transition to end native forest logging

While the government’s position on the proposed new parks isn’t the most ambitious or aspirational, we can not and will not let our elected representatives stall on their legislative and moral duty.

The Victorian National Parks Association community was instrumental in bringing home this long-fought for accomplishment. You helped forge a commitment to create the most significant addition to our parks estate in over a decade. This is no small feat – thank you. We hope you join us on the journey to make these parks a reality, for wildlife, habitat and people.

Did you like reading this article? You can read the latest full edition of Park Watch magazine online here.

Want to be kept up to date about this and other nature issues in Victoria? Subscribe to our email updates.

You can also receive our print magazine Park Watch four times a year by becoming a member. Find out more here.