PARK WATCH March 2020 |

Our native plants and animals have had a long and troubled parent-child relationship with fire. It might be becoming an irreconcilable one, writes VNPA Parks Protection Campaigner Phil Ingamells.

Since July last year, fires have burned through nearly 16 million hectares of Queensland, NSW, Victoria, WA, SA, Tasmania and the ACT. About 1.5 million hectares of that was in Victoria.

This has been, unquestionably, an unprecedented event since records have been kept. Some 3,500 homes have been destroyed and 33 people lost their lives. It was something of a miracle more lives weren’t lost.

The Australian flora we love, the eucalypts, bottlebrushes and more, have largely evolved in response to fire. Yet fire seems unsatisfied with that achievement; it will not abandon its harsh but nurturing role. It even seems to have taken vengeance on its creation, periodically burning the bush to a crisp and having a good go at us in the process.

Fire, this most primal of elements, this searing expression of the sun’s energy on Earth, is getting increasingly hard to live with.

It started late last year with the burning of the previously ‘unburnable’ subtropical rainforests of Terania Creek and Lamington National Park in NSW. Then, later that summer, as a final gesture, flames incinerated a great many pockets of East Gippsland’s warm-temperate rainforests and had a good bite at the Errinundra Plateau’s cool-temperate rainforests.

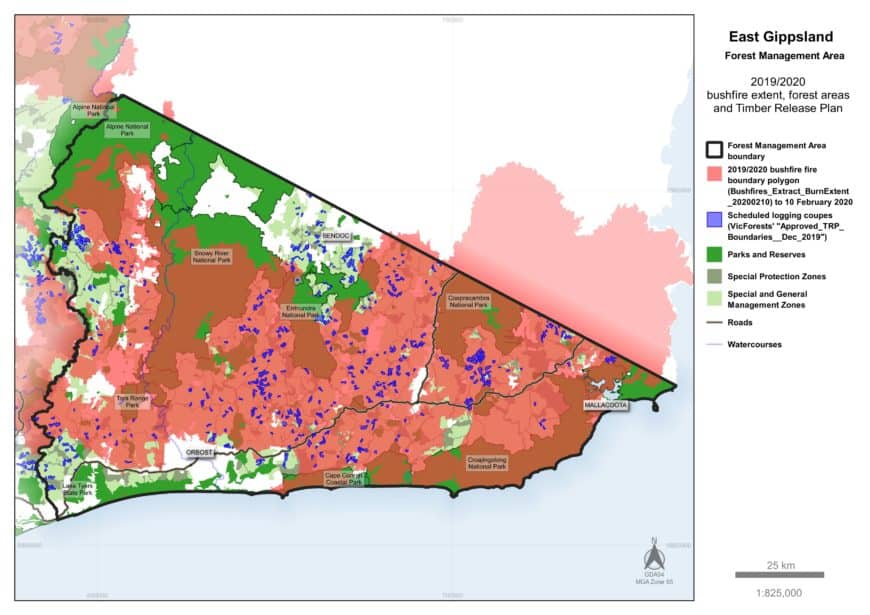

This summer’s fire through East Gippsland

The assault on our rainforests was just one of many impacts on nature, but perhaps the cruellest stroke.

Botanists know that ‘rainforest’ is a misnomer, and would rather call them ‘fire-free forests’. These ferny patches of green that we mainly find in sheltered valleys in Victoria are truly ancient forests. They are surviving patches of the great misty forests of Gondwana, the one-time single landmass of the Earth’s southern hemisphere.

Their canopy trees, like Lilly Pilly, Southern Sassafras, Muttonwood and Olive-berry, obligingly hold their leaves horizontally, sheltering a moist understory of even more ancient plants: an abundance of spore-shedding mosses and ferns, and their more primitive ancestors in turn. They are, indeed, living museums of ancient flora.

Now just tiny remnants of their former extent, these rainforests have been sheltering perilously from fire for some 45 million years. The flames that randomly trickled or roared through the newly evolved ‘Australian’ forests, dominated by more recently evolved plants like eucalypts and wattles, generally skipped over deep valleys leaving the Gondwanan forests unscathed.

Or, if fire did occasionally burn into these ferny dells, they would need a very long fire-free period to recover, not having evolved good fire-recovery strategies.

Victoria’s most extensive patch of warm-temperate rainforest, East Gippsland’s Jones Creek, burnt extensively in 1983, and a 2013 study of its recovery said that if another fire returned in less than 40–50 years, it would cause progressive decline, returning it to a eucalypt dominated forest. This summer’s fire has brought that scenario close.

It’s not just rainforests that have been hit by frequent fire; repeated blazes can seriously test the capacity of many of the fire-adapted species to hang on.

Snow Gums, the much-loved, beautifully twisted and gnarled eucalypt species of Victoria’s high country, can live for centuries. A Snow Gum can quickly resprout from a large underground lignotuber when an occasional alpine fire has killed the above-ground parts of the tree. Yet three fires in close succession can weaken and kill them. This scenario has happened now around The Horn in Mount Buffalo National Park, and in the southern parts of the Bogong High Plains in the Alpine National Park.

Victoria’s Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning’s biodiversity response crew has estimated that some 170 already rare or threatened species have been impacted by the roughly 1,500,000 hectares of this summer’s fires in eastern Victoria. They include animals like the Barred Galaxias, Long-footed Potoroo and Diamond Python, and plants like Buff Hazlewood and Betka Bottlebrush.

We are in a new paradigm. Climate change, and the more frequent fire it brings, is changing our landscape, and not over evolution’s necessary aeons; it’s happening now, before our eyes.

More

Read other articles in our Living With Fire feature: ‘The Next Fire’ and ‘Save Or Salvage‘.

Did you like reading this article? Want to be kept up to date about this and other nature issues in Victoria? Subscribe to our email updates.

You can also receive our print magazine Park Watch four times a year by becoming a member. Find out more here.