PARK WATCH Article June 2023 |

If offshore wind energy is to protect our planet, nature needs to be up front and centre. Marine spatial planning is a tool that can achieve this says Shannon Hurley

As plans to power Victoria with offshore wind energy develop, government leadership to properly protect our marine environment is not as breezily found. Victoria has ambitious plans to be a leader, but this shouldn’t come at the expense of nature and people’s livelihoods.

What are the current planning arrangements governing the industry, and where should they be if we’re to protect Victoria’s marine gems?

Building the offshore wind world

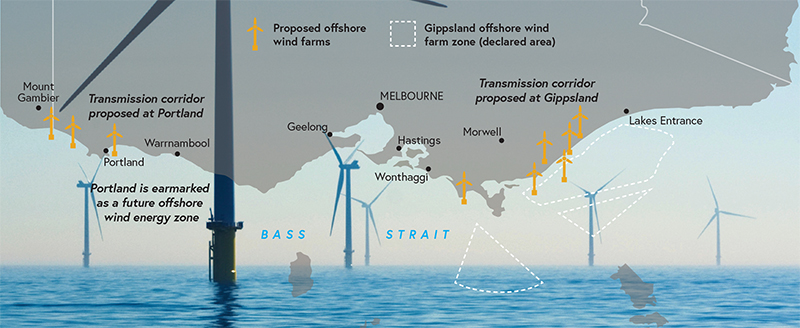

Offshore wind generation is where the wind turbines are mounted on the seabed. Other offshore assets like sea cables and substations to transform the power are included. The infrastructure is in Commonwealth waters (more than 5 km offshore), but the cables traverse into state waters to connect with the land.

The transmission network is required to transfer energy generated by the wind farm to the existing electricity transmission network. Two locations have been proposed to extend the network at Portland and Gippsland. VicGrid, within the Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action (DEECA), has been tasked with its development.

The Port of Hastings, known as the Victorian Renewable Energy Terminal, has been identified as the assembly port, providing support for wind farm construction and operation.

Potential impacts

There will be impacts from the construction and ongoing operation, some of which may include:

- Direct damage to habitats such as reefs.

- Direct collision, injury, or death of wildlife with infrastructure like albatross and other seabirds.

- Impacts from underwater noise on navigation of fish and marine mammals.

- Disruption to migration pathways, breeding, feeding and calving areas of wildlife like Southern Right Whales.

- Vegetation removal on land.

- Dredging impacts in Western Port Bay, should that be undertaken.

Capturing data and analysing the impacts on marine environments is challenging, As a result, there are still many unknowns.

The regulatory framework

The federal government is responsible for the over-arching framework and deciding how and where projects can operate. In December 2022, the Albanese Government declared the first offshore wind energy zone at Gippsland, which opened the door for companies to apply for a feasibility license and undertake studies. This year should reveal which ones get a license.

The Victorian Government’s job is more in the roll out, construction and support for projects. They have responsibility for the transmission network and port development.

All elements of the power supply chain will need to assess the environmental impacts before any construction begins. The Commonwealth will assess their jurisdiction across land and sea under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999, and the Victorian Environmental Effects Statement (EES) process covers the relevant areas within state waters and land.

While the transmission network and the ports development are government-led (by VicGrid and the Port Authority, respectively), it is disappointing to see the marine space is left to each offshore wind developer to do their own planning.

Once again, our marine environment is conspicuously absent. The danger is that energy companies may think they have a suitable site, when in fact they have not, which could result in a waste of time, enormous funds and effort if the area is later deemed unsuitable.

On land there are detailed planning schemes and laws that developers are required to work with in order to avoid infrastructure in certain places. This includes tenure arrangements such as national parks. These do not exist in the marine environment.

Just because wind turbines are located offshore does not mean their impact is nullified. The same level of care and the criteria we show for our land should also be applied to the marine world.

Lack of marine planning

Our unique marine world, above and below the surface, is exquisite. From critically endangered Southern Right Whales calving and splashing, to the sheer size of the wings of an albatross soaring the sky, to Kingfish schooling and darting as they catch a feed.

The energy and environment portfolios of government must come together effectively to plan for the protection of our marine world. Without coordinated upfront planning, clean technology designed to address the climate crisis could cause significant and unnecessary harm to reefs, wildlife, and habitat.

In a nutshell, the current system is not fit for purpose – especially when we’re talking about the establishment of a state-wide industry. It’s being squashed into existing assessment processes on a project-by-project basis. There’s no upfront planning, which is essential for the proper identification of suitable areas for new projects.

The Victorian Marine and Coastal Policy (and international guidelines) say marine spatial planning should be used to coordinate and guide planning, management, and decision-making across marine sectors in Victoria (like renewable energy).

VNPA is advocating for proper up-front marine planning. It is the only way for impacts across land and sea to be understood (and thus avoided) early on. The Victorian Government even developed a framework for exactly this – but has yet to get the ministerial tick of approval to implement it.

Marine spatial planning is a process that could be used to identify marine users and organise marine space in state and Commonwealth waters.

We’ve been advocating for clear criteria to oversee:

- Infrastructure through national and state parks, marine national parks, Ramsar areas, high conservation value areas.

- Areas marked to be new marine national parks.

- Culturally significant areas.

- Important feeding, breeding, calving and migratory areas.

- Visually sensitive areas or national parks like Wilsons Promontory.

Sustainable energy needs sustainable planning. Industry needs the help of marine spatial planning early on to guide initial site identification and safeguard our marine environment from harm.

Marine planning would help to develop a responsible industry. It just needs the seal of approval from both the environment and energy ministers to make it happen.

It’s our hunch that Portland could be the next area declared. It’s time to get our skates on. It doesn’t have to be perfect, but it has to get started.

Read our Winds of Change discussion paper

- Read the latest full edition of Park Watch magazine

- Subscribe to keep up-to-date about this and other nature issues in Victoria

- Become a member to receive Park Watch magazine in print