PARK WATCH June 2019 |

Ian Penna writes about what hasn’t happened in the past ten years.

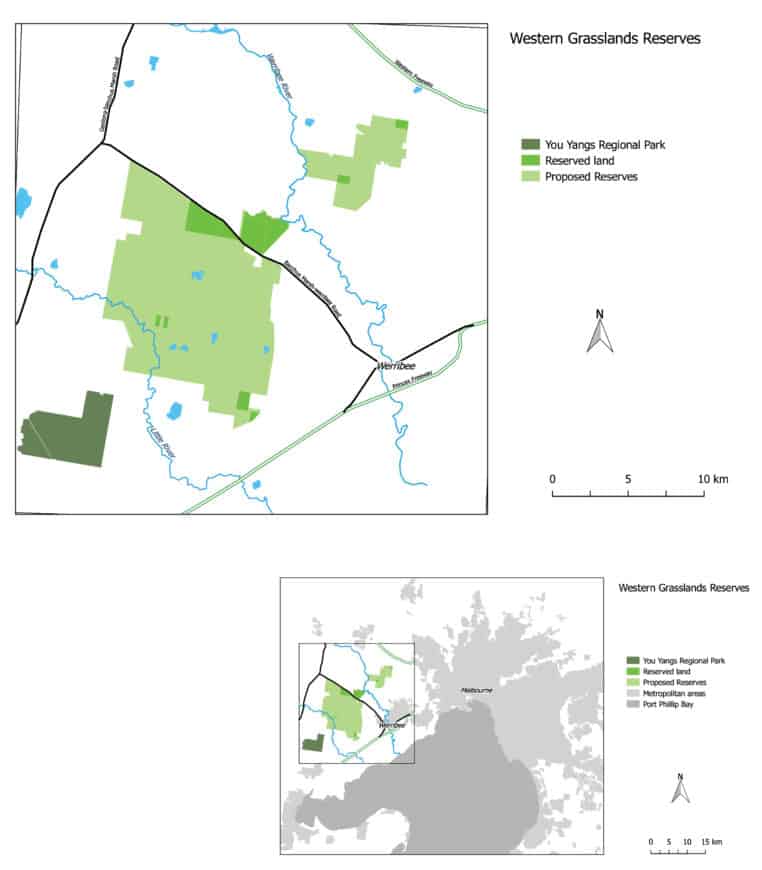

The Western Grassland Reserves were proposed to protect “the largest remaining concentration of volcanic plains grasslands in Australia and a range of other habitat types, including ephemeral wetlands, waterways, Red Gum swamps, rocky knolls and open grassy woodlands. The reserves will increase the extent of protection of Natural Temperate Grassland of the Victorian Volcanic Plain from two per cent to 20 per cent. The WGR also provides habitat for a large number of State and Commonwealth listed threatened and rare species” (Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning)

The ‘Western Grassland Reserves’ (WGR) proposal for the plains west of Melbourne is a serious failure in conservation policy creation and implementation.

Victoria’s conservation community needs to redeem what is left of it.

In 2009, the Victorian Government promised the Commonwealth Government it would establish two reserves by 2020 to protect and enhance the plains’ remnant grasslands, and offset grassland destruction by Melbourne’s creeping urban sprawl.

Creating the reserves by buying 14,405 hectares of private land, containing 10,091 hectares of endangered ‘grasslands’, was the centrepiece of commitments made by the state and federal governments through the Melbourne Strategic Assessment (MSA) program conducted under Australia’s Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation 1999 (EPBC Act).

Modelling concluded that the greatest conservation benefit would occur by creating the reserves as early as possible. However, to date, Victoria has only bought less than ten per cent of the planned reserves area. And the quality of much of the grasslands has been allowed to seriously degrade through the spread of noxious weeds.

Responsibility for this failure rests with successive state and federal governments, as well as the Victorian and Commonwealth public service departments that make decisions related to the WGR proposal.

The Commonwealth environment department performed a risk analysis of the MSA program, and in January 2010, advised the then minister, Peter Garrett, before he endorsed the Program, that it “considers that these risks have been adequately minimised …”

Nevertheless, failure was inherent in the initial WGR proposal because it was a political compromise with a poor funding model and weak enforcement protocols. Conservation groups made these kinds of points during the assessment process, but it is clear they were largely ignored.

The state government’s plan for raising funds to purchase, and initially manage, the reserves’ land was fundamentally flawed. It would get the money by forcing real estate developers clearing endangered grasslands closer to Melbourne’s expanding suburbs to buy theoretical ‘offset credits’ from the proposed WGR as compensation for this destruction. However, the state government has no direct control over developers’ decisions on what available land they will build houses – or when. It could not make developers clear specific grassland areas for its convenience. The state government seriously misjudged the rates of development and rushed the original assessment – only to see development rates drop off.

The reserves proposal began to unravel from 2010, the MSA program’s first year, because developers weren’t destroying enough remnant grassland for new housing estates, so didn’t buy sufficient offsets to generate the state government’s desired income. In 2012, Victoria admitted that it was not going to purchase all the land by 2020 because urban expansion was too slow. It asked the Commonwealth to extend the deadline without a specific target date.

A mere week later, the Commonwealth agreed “in principle to extension of the acquisition timeline …”. There was no public involvement or notification or reference to the conservation priority of establishing the reserves quickly. The Commonwealth expected to work with Victoria “to develop clear and transparent options to extend the acquisition timeframe for the Reserve”. Seven years later, this still hasn’t happened. In early 2019, a Commonwealth environment department representative stated that “no decision to vary the acquisition timeline has been made”.

No detailed economic analysis for the WGR has ever been published. Rough calculations indicate that recent offset prices/habitat destruction fees are probably far too low to purchase all the land and manage it to what might be expected to be a reasonable standard.

Also, the economics of the WGR has been sabotaged by Victoria’s failure to comprehensively tackle the area’s evolving weed problem; this will add to future management costs. Some land may not be salvageable.

A 2012 survey for the Victorian environment department showed that much of the WGR land was severely infested with Nassella weed species, including Serrated Tussock and Chilean needle grass.

Under the 2009 MSA program, Victoria had to prepare an interim management plan that would “introduce a management regime to ensure grassland areas are not degraded in the period prior to formal acquisition of the land for the grassland reserves”.

Protective actions that Victoria was meant to take included amending local planning schemes and legislation, making declarations to legally protect grasslands from weeds, undertaking works with landholders and local councils, and conducting on ground surveillance and enforcement. However, the 2016 ‘Serrated Tussock Seed Storm’ that spread serrated tussock seed across proposed WGR land and into surrounding areas challenges Victoria’s success in relation to this responsibility.

2010 departmental advice to the federal environment minister stated that if the MSA program “is not implemented as specified or the conservation outcomes are not obtained, approvals given for any actions relating to the non-compliance would become invalid”.

However, it also noted that: “There will in most cases be limitations on the ability of the Commonwealth Government to utilise existing enforcement mechanisms under the EPBC Act in instances where the Victorian Government fails to implement or comply with the program as required.”

The legal implications of Victoria’s failures over the WGR should be clarified by the relevant ministers. The degradation and loss of the WGR EPBC Act-listed grassland are intimately linked to protection and management. Continued state and federal inaction imperils remaining grasslands.

The voluntary Public Acquisition Overlay placed on the land proposed for the WGR had an impact on landowners by creating doubt about the future monetary value of their property. This probably led some to reduce or stop their weed control, while inhibiting innovative grassland management and restoration. An open-ended acquisition plan as desired by the Victorian Government perpetuates doubt over the grasslands’ future. It is the worst possible option.

With so much time passed, if the remnant grasslands across Melbourne’s western plains are to have a reasonable chance of being managed to achieve the social and environmental objectives for which the WGR were promoted, then the reserves proposal needs to be publicly scrutinised. An independent publicly funded review with strong community involvement needs to examine all options for creating new ecologically sound and financially secure futures for these endangered grasslands.

Did you like reading this article? Want to be kept up to date about this and other nature issues in Victoria? Subscribe to our email updates.

You can also receive our print magazine Park Watch four times a year by becoming a member. Find out more here.