PARK WATCH June 2019 |

VNPA Executive Director Matt Ruchel examines the third Victorian State of the Environment report released in March 2019 – and finds it presents a fairly grim picture for nature in Victoria.

A United Nations report released in May revealed that globally around one million animal and plant species are now threatened with extinction, many within decades – more than ever before in human history. The report warns that the rate of species extinctions is accelerating, and will likely have grave impacts on people around the world. Loss of biodiversity is shown to be not only an environmental issue, but also a developmental, economic, security, social and moral issue as well.

Alarming and depressing – but not a new story in Victoria, Australia’s most cleared state. The report comes on the back of the latest Victorian State of the Environment (SoE) report, which examined 170 indicators of environmental condition.

Worryingly, only 11% of these indicators were assessed as ‘good’. Some 37 % were ‘fair’; while 52% were definitely problematic, either ‘poor’ (32%) or ‘unknown’ (20%).

Only 10% of indicators showed ‘improving’ condition; 30% were ‘stable’; and 60% problematic (30% ‘deteriorating’ and 30% ‘unclear’).

Conservation of marine ecosystems in protected areas such as our network of marine national parks and sanctuaries is a little brighter, with the status of protected areas across the state listed as ‘fair’, but with clear condition issues identified in the Gippsland Lakes and East Gippsland inlets.

The outlook was poor for the assessment of the impacts of fisheries production on the marine environment. Only poor-quality data is available to assess changes in stocks, impacts on habitats and interactions with threatened species.

There are still significant gaps in the protection of habitats and species in our current network, which fails to meet international targets. A more comprehensive State of the Marine Environment study is planned as a stand-alone report in 2021.

For an advanced, wealthy and self-proclaimed progressive state like Victoria, I am not sure which is worse: ‘deteriorating’, ‘poor’ or ‘unknown’. The fact that repeated SoE reports often do not have the data to answer even basic questions about the health and trends in our environment is as big an indictment as continuing to let key natural areas decline.

This is not the fault of the report’s authors.

The report is developed by the Commissioner for Environmental Sustainability Victoria. Supported by her small team, the Commissioner, Dr Gillian Sparkes, produced not only the State of the Environment report, but also, for the first time, the State of the Forests and the State of the Yarra and its Parklands reports. The Commissioner’s office largely depends on interpreting data from various state government agencies and some academic literature.

The indicators used apparently align Victoria’s environmental reporting with international frameworks, including the United Nation’s System of Environmental Economic Accounts (SEEA) and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). However, it is not always clear what the indicators actually indicate.

The aim of the SoE is to provide independent and objective scientific reporting to inform policy-makers, scientists and the wider Victorian public on the state of the state’s natural environment. According to the Commissioner for Environmental Sustainability Act 2003, the Commissioner’s role is to:

- review and report on the condition of Victoria’s environment

- encourage decision-making that facilitates ecologically sustainable development

- enhance knowledge and understanding of issues relating to ecologically sustainable development and the environment, and

- encourage Victorian and local governments to adopt sound environmental practices and procedures.

The Act requires the SoE report to be tabled in parliament, and the Victorian Government to table a response. But the responses are often pedestrian, often agree ‘in principle’, or are just a rehash of existing programs. This is a structural flaw in how the legislation operates, and it’s an indictment of our political culture. A state institution set up to inform the state of significant problems should not be largely ignored when it makes recommendations for improvements.

The importance of private land conservation

The only glimmer of light was one improving trend – in private land protection – due to the increase in people applying for Trust for Nature conservation covenants to protect bushland on their properties in perpetuity.

One of the strongest recommendations in the 2019 SoE report is for private land conservation.

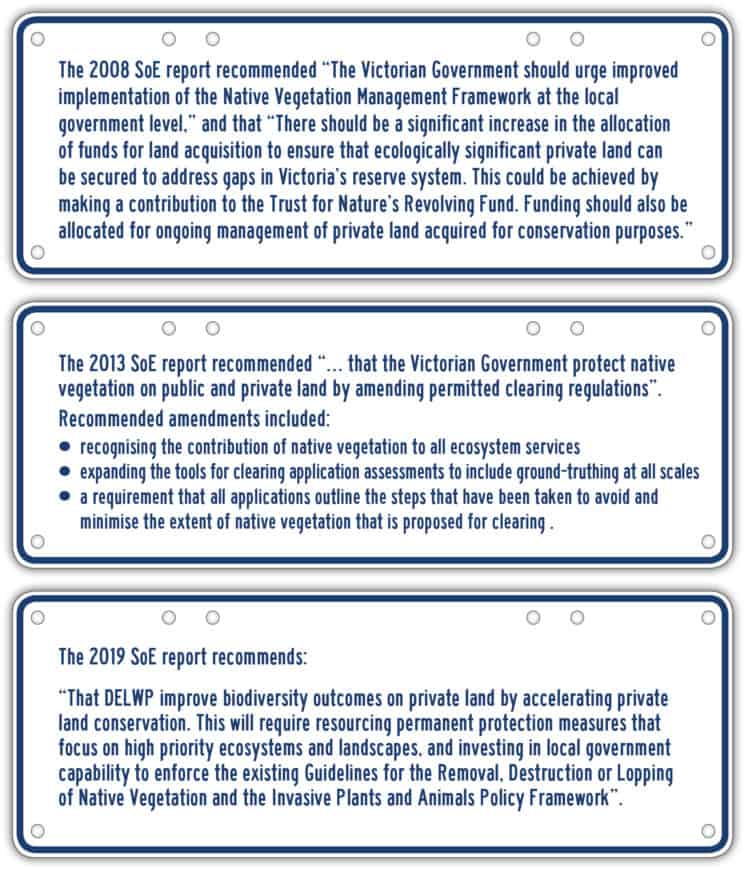

However, similar recommendations have appeared in both previous SoE reports from 2008 and 2013. See boxes below for a comparison.

Some elements of these recommendations at left were adopted in the review of the Native Vegetation Clearing Regulations in 2014–2017 – though nowhere near fully.

Despite the recommendations, in general the poor and declining condition of our natural environment has now been a finding of successive SoE reports.

A chief biodiversity scientist

Another of the key 2019 recommendations is the better coordination and application of science, by the appointment of a Chief Biodiversity Scientist. Currently, much of the scientific research undertaken by government agencies and the data collected is poorly coordinated, with one arm of the same department doing something different to another or, often, nothing actually happening at all. Across the whole of state government, the situation is worse.

The 2019 SoE report recommended “That DELWP streamline the governance and coordination of investment in the science and data capability of all government biodiversity programs and improve the coherence and impact of the publicly-funded, scientific endeavour. Further, that DELWP establishes the position of the chief biodiversity scientist to oversee this coordinated effort and provide esteemed counsel to the DELWP Secretary and the Minister for Environment to improve the impact of investment in biodiversity research across the Victorian environment portfolio. Additionally, that DELWP improve biodiversity outcomes on public land by streamlining and coordinating governance arrangements.”

This recommendation does not sound exciting, but is profoundly important. If we are really going to respond to the ongoing decline in nature, in the face of unprecedented population growth and increasingly dramatic climate change, the scientific building blocks must be solid, irrefutable and, most of all, coherent and communicable. Otherwise, all we can look forward to is the ongoing decline in our natural heritage. That’s not an acceptable situation.

VNPA’s team of nature campaigners are meeting regularly with Victorian Government ministers, their advisors and department officials advocating for protection of nature, including for the SoE recommendations to be adopted in full. This is only possible thanks to the backing of our financial supporters. Join us in campaigning for the protection of nature, the amelioration of structural flaws in legislation, and improved investment in biodiversity research and protection by making a tax-deductible donation today.

Matt Ruchel, VNPA Executive Director, is a member of the Commissioner for Environmental Sustainability’s Reference Group.

Did you like reading this article? Want to be kept up to date about this and other nature issues in Victoria? Subscribe to our email updates.

You can also receive our print magazine Park Watch four times a year by becoming a member. Find out more here.