PARK WATCH June 2021 |

Evidence against Victoria’s fuel reduction program is clear, yet burns are increasing. Calls for a pause and re-assessment of fire management are growing louder, says Phil Ingamells.

The most alarming thing about “fuel reduction” burning is that it is often fuel production burning.

The next most alarming thing is that the state government department that plans and performs those burns doesn’t monitor what actually happens afterwards. Anyone marketing a car, a vaccine, or building cladding would be expected to know how it performs over time, whether it’s safe, and, of course, if it actually works.

However, Victoria’s Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP) doesn’t return to the site of

its fuel reduction burns and record what has eventuated – not after one year, not two or, most importantly, not a decade or so into the future.

That’s not just alarming, it’s downright puzzling, because DELWP boasts of the efficacy of its ‘Monitoring, Evaluation and Reporting’ framework; the department claims it monitors performance and learns from what it does, allowing it to improve performance.

It might seem odd to say that a fuel reduction burn increases fuel. But then it once seemed odd to say that the earth wasn’t flat, but a ball floating in space.

The first clear statement of this situation came from Judge Stretton’s Royal Commission into the 1939 Black Friday bushfire that roared through some two million hectares of forests and scrub.

Referring to the common practice at the time of burning open forests and woodlands to produce green pick for cattle and sheep, Stretton said:

“The fire stimulated grass growth, but it encouraged scrub growth far more. Thus was begun the cycle of destruction which can not be arrested in our day. The scrub grew and flourished, fire was used to clear it, the scrub grew faster and thicker, bush fires, caused by the careless or designing hand of man, ravaged the forests; the canopy was impaired, more scrub grew and prospered, and again the cleansing agent, fire, was used. And so today … the wombat and wallaby are hard put to it to find passage through the bush.”

That was pretty controversial at the time, but in 1946 Stretton reinforced his claim in a second Royal Commission, this time into forest grazing. On his recommendation, the right to burn was taken away from those holding a grazing licence. Burning was to be the sole responsibility of the government’s Forest Commission.

But since those days, a land management body that primarily practised the burning of ridgetops to protect a timber supply has transformed itself into a large, heavily equipped, paramilitary organisation that seems intent on frying the state.

And this organisation, charged with protecting our lives and nurturing our natural heritage, has largely been left to report on its own performance.

Last year, however, following the third time in 20 years that a one-million-hectare wildfire tore through Victoria’s bushland, two independent inquiries have brought DELWP’s management into question.

Among issues raised in the Inspector General for Emergency Management’s report was the observation that:

“Even with an extensive fuel management program, bushfire risk remains as the vegetation regrows.”

That statement is quite scathing of DELWP’s burn operations, and can be strongly backed up by recent independent research.

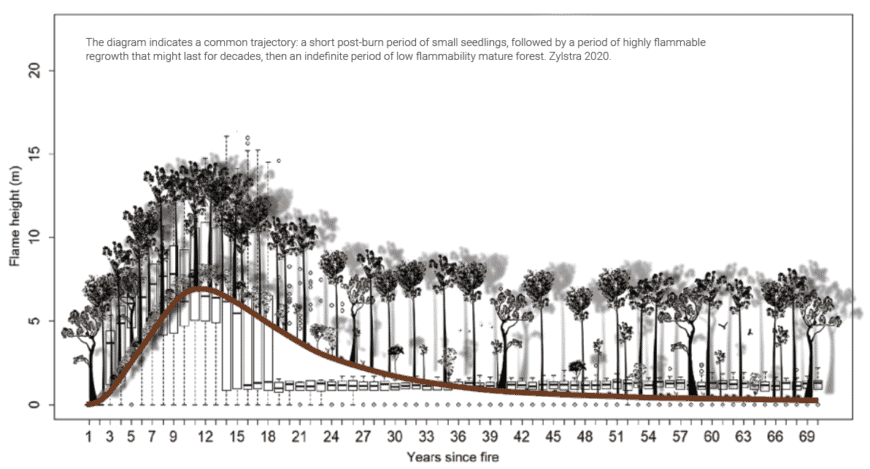

In a submission to last year’s Federal Royal Commission into Natural Disaster Arrangements, Associate Professor Philip Zylstra, Professor David Lindenmayer and colleagues illustrated their argument with a diagram showing how fuel flammability can actually increase for 30 years or more after a fuel “reduction” burn.

The bush responds in complex ways to fire, as changes in species and forest structure depend on many factors, but empirical evidence now supports long-standing observations that burns can increase understorey flammability for decades.

In a parallel inquiry by Victoria’s Auditor General, another astonishing statement appeared:

“With the exception of some isolated cases studies, DELWP does not know the effect of its burns on native flora and fauna”. (See Park Watch December 2020 for more statements from fire inquiries.)

DELWP has been relying on its ever more sophisticated computer modelling to manage fuel, protect lives and save our natural heritage, but recent burns show a serious lack of response to old fashioned, on ground observation.

After the Black Summer of 2019–20, when vast areas of East Gippsland went up in flames, DELWP’s biodiversity arm called for the protection of remaining wildlife habitat refuges in the east.

But rather than scaling back burns, DELWP’s fire management arm continued or even increased its program. And logging also continued apace. (See ‘After the fires’ Park Watch March 2021)

Perhaps the most striking example of DELWP’s data-based blindness was when, despite clear calls to protect remaining unburnt Sheoak stands, the seeds of which are essential food for Glossy Black Cockatoos, and despite plenty of advice from ornithologists that Glossy Blacks were highly dependent on any remaining food source, DELWP decided to continue its planned burn of a remaining stand. Or rather it burnt half the stand, on just one side of the road, because a Glossy Black was only recorded on its database on the other side of the road.

We need regular independent scrutiny of DELWP’s fire management. And we need a department that has the will and capacity to implement real change.

Did you like reading this article? Want to be kept up to date about this and other nature issues in Victoria? Subscribe to our email updates.

You can also receive our print magazine Park Watch four times a year by becoming a member. Find out more here.