PARK WATCH Article September 2023 |

Executive Director, Matt Ruchel, unpacks the imminent end of an intractable industry

It was indeed a long-awaited and welcome milestone, when on 23 May the Andrews Government announced the end of native forest logging in Victoria. This has come after decades of community struggle against the industrial logging of our native forests.

Largely unequivocal, the announcement still raises some questions about future processes and decisions still to be made.

Speeding up the transition

The Andrews Government made it clear their decision to bring forward the transition was to remove ‘… the uncertainty that has been caused by ongoing court and litigation process and increasingly severe bushfires …’. They also noted that ‘there are no options for regulatory reform’.

The fact is that most logging in the state’s east had been on hold for six months. This was due to multiple community court cases against VicForests and the closure of the native-forest-eating white paper machine at the Opal Australia Paper mill. Combined these factors proved to be the final nails in the coffin of this widely unpopular and damaging practice.

Key points in the premier’s media release included the ‘…transition away from native timber logging earlier than planned – by 1 January 2024’. This is an important commitment, grounded in a firm date.

Workers and industry will be supported through an $875 million transition package that includes:

- Victorian Forestry Worker Support Program.

- Sawmill Exit Payment or Sawmill Voluntary Transition Package to compensate sawmills.

- Forestry Transition Fund to provide grants of up to $1 million to expand, diversify or start new businesses.

Harvest and haulage (usually the machine operators who actually cut the tree down and truck drivers who take them for pulp or sawlog) were not eligible for payouts. Instead, they would be redeployed in the delivery of strategic fuel breaks, ongoing recovery works on public land and the treatment of hazardous trees in the preparation of planned burns and along critical firefighting roads and tracks.

A later statement clarified this with a Harvest and Haulage Support Package made available for forest contractors, which includes contract and equipment compensation and worker redundancy payments. Harvest and Haulage would also be eligible for Timber Innovation Grants to change sectors, with government clarifying they will continue to consult with forest contractors about retaining them for ongoing management of public land (with genuine opt-out packages available for those who choose to exit). We understand there are about 30 harvest and haulage contracts across the state.

The scope of the announcement unpacked (Warning: technical information!)

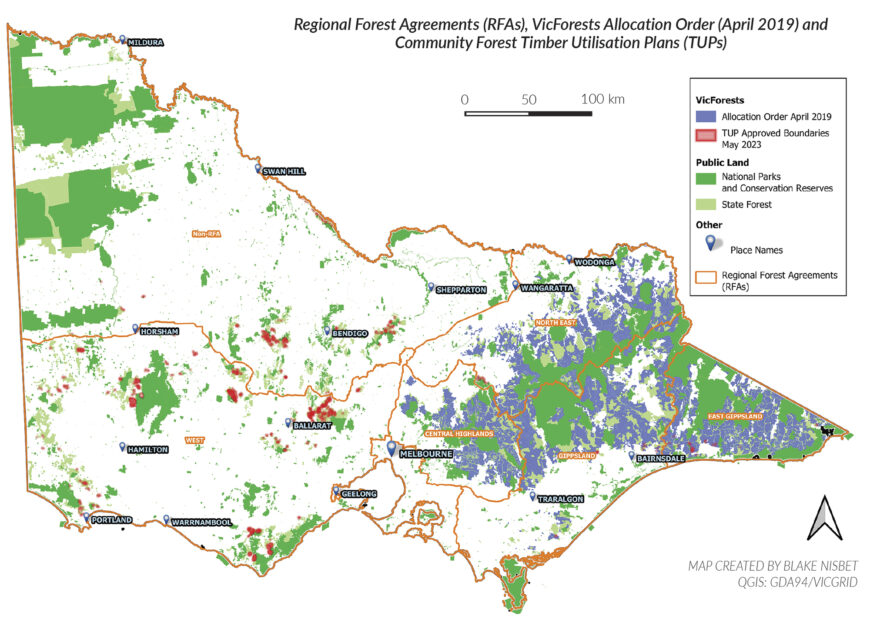

The phase out was linked to 1.8 million hectares of forest covered in what’s called the allocations order. This is a legal instrument under Part 3 of the Sustainable Forests (Timber) Act 2004, which defines a forest area. Once the order is issued, the timber allocated becomes the property of VicForests. This is restricted to the east of the state (technically called the ‘Eastern defined forest area’) and logging schedules are typically called Timber Release Plans.

VicForests can only operate outside of an Allocation Order if issued a Forest Produce Licence under section 52 of the Forests Act 1958 by the minister for the environment or delegate. This is what happens in western Victoria, and some smaller areas in the east. The logging plans are formalised through a schedule called the Timber Utilisation Plan (TUP).

What about the west?

The current TUP covers 124 logging areas totalling approximately 65,000 hectares, in west and north, with some areas in the east bigger than Wilsons Promontory National Park. It also includes clearfell operations in Mt Cole, storm clean operations in the Wombat Forest and other logging in some of the most fragmented forests in the state.

The statement that ‘The government will be required to deliver a program of land management works to manage the 1.8 million hectares of public land currently subject to the timber harvesting allocation order’ leaves unanswered questions about the forests of the west, and logging under forest produce licences.

In the Victorian Parliament, Ellen Sandell, Greens Party environment spokesperson and Member for Melbourne, sought clarification about the status of the west. She directed her questions to the Minister for Agriculture, Gayle Tierney at the Public Accounts and Estimates Inquiry into the 2023-24 budget estimates on 6 June 2024.

A spokesperson for the minister responded ‘… they operate under a forest produce licence. There are about 50 licences that are current. Most of those will expire in the end of June next year, June 2024. They will be managed as a separate decision that needs to be made about the ongoing community forestry part of that.’

Alarm bells ring around ‘community forestry’ loophole

This set off alarm bells for VNPA. While this is a smaller area than the east, continuing logging in the west, and keeping in place a mechanism for logging that could be used right across the state, creates a major loophole. This is alarming as since VicForests took control of the so called ‘community forestry’ operation in 2014, there has been a 52 per cent increase in coupe areas listed under the TUP since 2017.

While there are currently around 55 licenses and 40 jobs, much of the forest to be logged is for low value uses like firewood. However, since 2008, sawlog extraction has increased 300 per cent in the west. So called ‘Community Forestry’ is taxpayer subsidised and runs at a loss. In 2021–22 revenue was $0.5 million against a program cost of $1.1 million with the shortfall funded by a state government grant. A familiar story of loss-making forestry.

What’s more important is that native forest and woodland logging occurs in highly fragmented landscapes in some of the most cleared areas of the state. There are large numbers of threatened animals, and more nationally-listed wildlife than in the state’s east. According to 2017 VNPA analysis Western Forests & Woodlands at Risk:

- More than 20 threatened native animals and 14 threatened native plants were found in or closely adjacent to a third of all proposed logging areas. These include Grey Goshawk, Regent Honeyeater, Little Egret, Swift Parrots, Powerful Owls, Brush-tailed Phascogales, Long-nosed Potoroos and Southeastern Red-tailed Black Cockatoos.

- Threatened wildlife has been found either within or near 33 per cent of planned logging coupes. In some forest management areas, including the Portland Forest Management Area, that figure leaps to 67 per cent.

- Seventy per cent of the area targeted for logging contains native vegetation types that are either endangered (19 per cent), vulnerable (11 per cent) or depleted (40 per cent). In the Horsham Forest Management Area, 54 per cent of vegetation is endangered.

We wrote our concerns in a letter to the Premier, and ministers for the Environment and Agriculture. The Minister for Agriculture clarified in correspondence that existing small-scale operations under Forest Produce Licences will continue until their expiry in June 2024. This was confirmed in a letter from the DEECA’s Secretary, on behalf of the Premier and Environment Minister, assuring us that native timber logging would end in 2024, including VicForests’ commercial operations under the Timber Utilisation Plan. The closure of commercial operations was also flagged in statements from VicForests.

A government announcement on 23 August 2023 saw community forestry sector become eligible for the expanded Worker Support Payments, and redundant equipment compensation, plus payments for under-supplied timber, and a one-off hardship payment.

So, while commercial forestry will end in June 2024, an intent to continue some sort of timber extraction in the forest remains. Activities like seed collection and regenerating areas after logging are cited as examples, but as yet there doesn’t appear to be any firm plans.

The critical question is now: happens next and how will our forests be managed into the future. There are some who see this as way of continuing forestry, who see restoration as another form of extraction, logging under another guise. This is sometime framed as ecological logging or thinning, or even fire mitigation where wood is just a by-product and need to be used for its ‘best possible use’. It all hinges on the intent, purpose and methods employed, which there are a spectrum of views and approaches.

In a world facing dramatic shifts in climate there is a need for forests and woodlands to be actively managed for ecological and cultural purposes. This requires resources, science and knowledge, and doing work that is properly monitored, evaluated, overseen and regulated.

What’s next?

The government’s public statement committed to ‘…an advisory panel to consider and make recommendations to government on the areas of our forests that qualify for protection as National Parks, the areas of our forests that would be suitable for recreation opportunities – including camping, hunting, hiking, mountain biking and four-wheel driving – and opportunities for management of public land by Traditional Owners.’

This appears to be similar to the process Eminent Panel for Community Engagement set up to consider Immediate Protected Area, such as Strathbogies and Mirboo North. This included a VEAC assessment and panel and relevant First Nations representation, to undertake community consultation and makes recommendations.

In March 2023, VEAC was requested to assess the values of the Immediate Protection Areas in the Central Highlands and East Gippsland, and adjacent state forests. A report on the values should be completed by 30 September 2023 with a final report by 30 April 2024. The area defined for assessment appears broader than the Immediate Protected Areas announced in 2019.

There is no detail on who might be involved in this panel or a timeline for its establishment, or even if the existing panel is still operating. Whatever the process they have an incredibly important job and the right mix of expertise is essential if they are to be successful.

The future of disgraced taxpayer-funded VicForests and legislation like the Forests (Wood Pulp Agreement) Act 1996, (which in many ways drove unsustainable logging, particularly in the Central Highlands) is also uncertain.

To properly manage our future forests our leaders must:

- Align the phase out of ‘community forestry’ with the rest of native forest logging under the allocation order, by 1 January 2024.

- Liquidate/abolish VicForests by 1 January 2024.*

- Commit to no logging within the promised central west parks and IPAs, effective immediately.

- Legislate the central west parks by 1 January 2024.

- Develop and release a science-based proposal for ecological restoration and ‘program of land management works’ across Victoria’s forest estate.

- Fast-track a qualified and well-resourced assessment process within two months to ‘…consider and make recommendations … on the areas of our forests that qualify for protection as national parks…’

- Remove legislation and agreements that enable native forest destruction such as the Forests (Wood Pulp Agreement) Act 1996 and the Regional Forest Agreements.

- Put in place regulation and independent regulatory oversight of Forest Fire Management Victoria.

*On 5 September, the government took what appears to be the first step around the future of VicForests by changing its status from a stand alone state-owned enterprise to that of a ‘reorganising body’. This allows them to make changes to its constitution, governance arrangements and capital structure.

- Read the latest full edition of Park Watch magazine

- Subscribe to keep up-to-date about this and other nature issues in Victoria

- Become a member to receive Park Watch magazine in print