PARK WATCH September 2020 |

Following Matt Ruchel’s reflection on the tenth anniversary of the Red Gum Parks in the previous edition of Park Watch, Professor Jamie Pittock from The Australian National University outlines his fears for their future.

As a scientist concerned for conservation of biodiversity, I rejoiced at the designation of 215,000 hectares in over 100 parks along the rivers of northern Victoria ten years ago.

Efforts to establish co-management of these parks with the Indigenous Traditional Owners is another notable step to address the wrongs of the past.

However, park declaration is only one step towards conserving these floodplain wetland ecosystems. Unless they are adequately watered, they will die. Their survival is being jeopardised by government mismanagement and climate change.

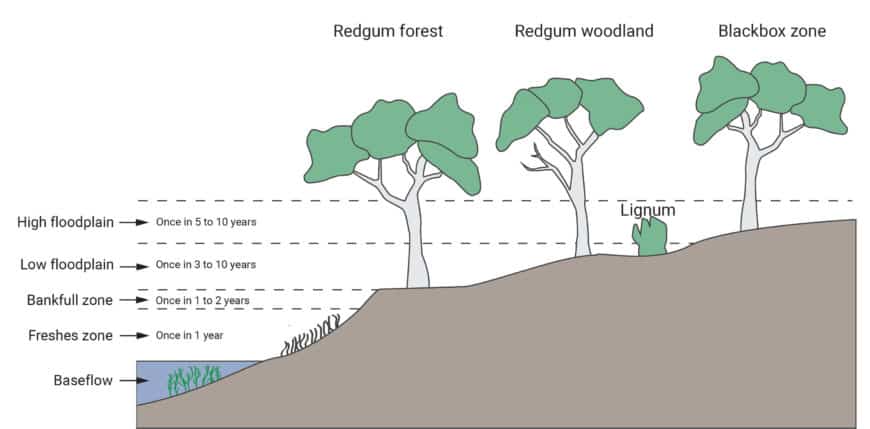

Different floodplain wetland ecosystems need to be inundated at different annual frequencies to remain healthy. Watering these ecosystems requires enough water to fill the river channel and then spill out over the floodplain. If the watering is too infrequent, the wetland vegetation dies, transitions to a dryland ecosystem, or becomes hypersaline or acidic.

The impacts of climate change are already being witnessed in our rivers, with reduced inflows. In addition to direct loss of water, river inflows are threatened by other risks, including capture in farm dams, the greater evapotranspiration from the catchment from forests regrowing after fires, and from biodiversity restoration plantings and commercial plantations.

However, I am most worried about the conservation measures that our governments can control and promised to implement in the Murray-Darling Basin Plan by 2024 – but have not delivered.

The Murray-Darling Basin Plan was adopted in 2012 by the Australian Parliament with the concurrence of state governments to manage water resources that “balances social, economic and environmental demands” – ostensibly to return the Basin’s freshwater ecosystems to health.

A seemingly obvious major failure in the Basin Plan is it made no direct allowance for climate change. And while the Basin Plan reallocates some water to the environment, it is not possible to conserve all floodplain wetlands with less than three fifths of river inflows left after diversions for irrigated agriculture. The wetlands to be conserved versus those to be sacrificed have not been clearly identified. Two government strategies – one good and one bad – are particularly important.

The good: reconnecting rivers to their floodplains

Known as ‘constraints relaxation’ in the obtuse jargon of the sector, in 2013/14 our governments agreed to restore seven major floodplains, including along the Goulburn and Murray rivers, in the ‘Constraints Management Strategy’. Roughly $840 million is allocated to compensate around 3,300 farmers for periodically flooding their riverside paddocks, moving infrastructure and to improve roads, bridges and levee banks. Around 375,000 hectares of floodplains would be restored – along the Goulburn River in Victoria, 12,000 hectares (92 per cent) of floodplains would be restored.

But our governments have done little to fulfil these commitments. Instead, the Victorian Government is not allowing managed water out of river channels for fear of compensation claims from landholders.

The bad: re-engineering floodplains for artificial ponding

Another jargon warning: these projects are referred to as the ‘environmental works and measures’ component of the ‘Sustainable Diversion Limit Adjustment Mechanism’ strategy in the Basin Plan. In Victoria, this involves construction of $281 million in pumping stations, levee banks and water regulators (small dams) in nine areas covering nearly 62,000 hectares in river-side parks – from Gunbower National Park to the border of South Australia – by 2024. Water from the River Murray channel would be diverted and artificially ponded on areas of floodplain to mimic natural floods.

There are a number of reasons for being gravely concerned about this strategy.

Only a little over 14,000 hectares would be able to be actively inundated with the infrastructure, at an exorbitant capital cost of nearly $22,000 per hectare. Using such infrastructure means relying on Victorian Government agencies to undertake expensive operation and maintenance measures every year forever.

Meanwhile, artificial ponding this water on the floodplain will not actually replicate vital ecological processes.

The ‘Sustainable Diversion Limit Adjustment Mechanism’ was a trade-off promoted by the Victorian and NSW governments for projects that purported to conserve biodiversity with less water. Consequently, the Commonwealth agreed to reduce planned water recovery for the environment by 22 per cent (605 billion litres) in the final Basin Plan.

It is unclear what the environmental objectives are for these ‘environmental works and measures’ projects. The governments have not argued that representative conservation of wetland ecosystems would be improved – and it would certainly be difficult to artificially water the ecosystems that sit higher on the floodplains. Originally the governments claimed the projects could help maintain core wetlands in drought. Unofficially, some government officials argue that the projects are for triage – to conserve remnant wetlands in the face of severe climate change. Regardless, the area of wetlands conserved by this strategy would be small. Worse, the more frequent and small environmental watering targets for the floodplain ecosystems bear no relationship to the less often but much larger ‘stream flow’ targets at the ‘hydrologic indicator sites’ that the overarching Basin Plan is intended to achieve.

Current Victorian Government focus on the Sustainable Diversion Limit Adjustment Mechanism over the Constraints Management Strategy means that the major area of wetlands in the Red Gum Parks floodplains may only be conserved accidentally by unmanaged floods.

The Victorian Government must deliver on the ‘constraints relaxation’ and reconnect the Goulburn and Murray rivers to their floodplains. And ‘environmental works and measures’ project approvals currently underway need to be reconsidered. Lastly, the revision of the Basin Plan by 2026 must also address the issue of which wetlands will be conserved and with what volume of water in a changing climate.

The future of the Red Gum Parks depends on how well they are watered.

Did you like reading this article? Want to be kept up to date about this and other nature issues in Victoria? Subscribe to our email updates.

You can also receive our print magazine Park Watch four times a year by becoming a member. Find out more here.