West Coast Port Phillip Bay

Often referred to as the Geelong Arm of Port Phillip Bay, the south-western end of Port Phillip Bay has an amazing and productive marine environment. This area is home to mangrove communities, saltmarsh areas, seagrass meadows, drift algal beds, shallow rocky reefs and internationally significant waterbird habitats.

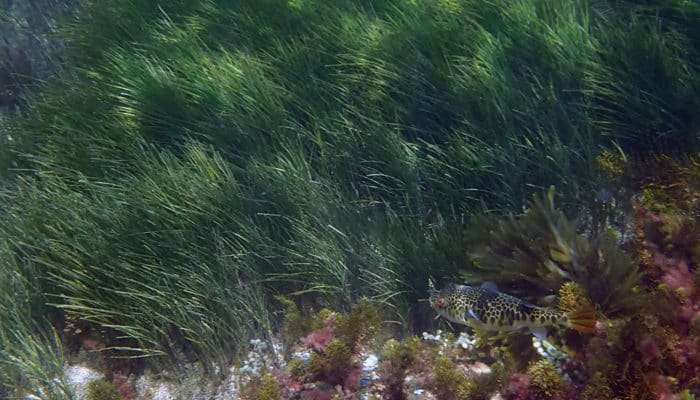

Shallow seagrass beds line the southern and northern shores of the Geelong Arm of Port Phillip Bay. The intertidal and subtidal seagrass meadows of Heterozostera tasmanica and Zostera muelleri off Clifton Springs and along the coast from Point Lillias to Kirk Point are important nursery areas for juvenile fish, including commercially important species such as King George whiting (Sillaginodes punctata). These seagrass beds are of very high conservation value and are incredibly productive, supporting a variety of marine and estuarine species. A threatened snapping shrimp also makes its home in this sheltered environment.

The shallow Corio Bay, less than nine metres deep, includes a Ramsar site from Limeburners Bay to Point Wilson and at the northern end of Geelong Arm (including The Spit Wildlife Reserve). Limeburners Bay, a funnel shaped estuary at the mouth of Hovells Creek is one of three remaining mangrove communities in Port Phillip Bay. Saltmarsh habitats are also found in Limeburners Bay, and from Point Lillias to Point Wilson. Saltmarsh are an important habitat for the endangered orange-bellied parrot (Neophema chrysogaster).

A unique drift algae community thrives in the sheltered environment of Wedge Point, while a little further to the northwest the Werribee River estuary is an important habitat for waterbirds.

Southern Port Phillip Bay

Southern Port Phillip Bay including Port Phillip Heads is one of the most treasured marine environments in Victoria. Within this region are six fully-protected marine areas that make up the Port Phillip Heads Marine National Park.

A dramatic underwater canyon, tall kelp forests, colourful sponge ‘gardens’, seagrass meadows, expansive sandy plains, surging currents and tranquil bays and backwaters – this area has them all. The diversity and abundance of marine plants and animals is immense.

Strong tidal currents occur at the Heads. Depending on the tides, currents into and out of the Bay can ‘run’ at up to 3 m per second under normal conditions but exceed 4.5 m per second in extreme conditions. The underwater canyon at the entrance to the Bay is known as the ‘The Rip’. This deep U-shaped feature is approximately 300 m wide and up to 90 m deep. The steep-sided drop-offs, gullies, rubble slopes, pinnacles, ridges, overhangs and associated fast-flowing tidal currents make it a unique marine area in Victoria and southern Australia.

The prolific and highly diverse sponge ‘gardens’ on the vertical reef faces, crevices, and deep caverns at Port Phillip Heads are nourished by the abundance of floating food swept with the currents. The sponge ‘garden’ communities include an array of soft corals, hydroids, jewel anemones and sea tulips that are visually spectacular on a national scale.

There is amazing biodiversity in the habitats of Southern Port Phillip. The intertidal rock platforms at Point Lonsdale and Point Nepean are home to the highest diversity of marine invertebrates of any sandstone reef in Victoria. Over 118 seaweed species have been recorded at Port Phillip Heads, comprising 53 species of red seaweed species, 48 brown seaweed species and 16 green seaweed species.

Small forests of the giant kelp Macrocystis pyrifera may be found at the Heads, although these forests have declined significantly in the area over the past 30 years. These forests have been known to grow to over 10 m in height in the area.

A high diversity of resident fish species live in Southern Port Phillip Bay, including more than 43 species. It is possible to see over 20 species in one dive. The main species include wrasses (e.g. Notolabrus tetricus, N. fucicola and Pictilabrus laticlavius), herring cale (Odax cyanomelas), sea sweep (Scorpis aequipinnis), magpie morwong (Pseudogoniistius nigripes), six-spined leatherjackets (Meuschenia freycineti), and Victorian scalyfin (Parma victoriae). Populations of the Southern Blue Devil (Paraplesiops meleagris) exist on the deep reefs of the area. Port Phillip Heads is considered an important stronghold for Victoria’s population of this territorial and beautiful fish.

Extensive shallow reefs at Point Nepean support a variety of marine life including Victoria’s marine state emblem the weedy seadragon (Phyllopteryx taeniolatus), cuttlefish and numerous seaweed and invertebrate species. Significant seagrass meadows of sea nymph (Amphibolis antarctica) also exist in the area.

Popes Eye, a small horseshoe-shaped ring of bluestone blocks constructed between Queenscliff and Sorrento is the only site in Victoria where fishing has been prohibited for an extended period (since 1979). Fish are very abundant and include wrasse, morwongs, old wives, scalyfin and perch.

The Portsea Hole, about 500 m from the Portsea Pier, is a remnant of the old Yarra River valley. The top of the hole is at about 14m in depth but drops rapidly to approximately 33m in depth. Popular with divers, it has abundant fish, encrusting algae, sponges, and soft corals.

A population of about 120 Burrunan dolphins (Tursiops australis) lives in Port Phillip Bay. The dolphin population relies on feeding opportunities presented by migratory species such as squid, mullet and barracouta that move through the Bay’s entrance.

The area is also renowned for its diversity of migratory wader birds. Swan Bay is an internationally significant shorebird habitat for resident and migratory species. Combined with Mud Islands, it is the second most significant site for shorebirds in Victoria (after Corner Inlet) and a key wintering site for the critically endangered orange-bellied parrot (Neophema chrysogaster). Swan Bay’s significant seagrass meadows are dominated by sparse beds of Zostera/Heterozostera seagrass. These areas are an important nursery area for King George whiting (Sillaginodes punctata), leatherjackets, black bream, garfish and flathead. Spotted pipefish (Stigmatopora argus) are also common. Forty-four fish species have been recorded in Swan Bay. Black swans also feast on the seagrass meadows.

The fine sands and muddy sediments around Mud Islands are an important habitat for many invertebrate species, including small crustaceans and segmented worms that, in turn, are food for many birds, including endangered and migratory species. The dense seagrass beds both within and around Mud Islands provide important feeding and nursery areas for fish species such as King George whiting. Several species of sharks including the bronze whaler (Carcharhinus brachyurus) are known to commonly bask in the shallow waters surrounding Mud Islands.

Marine Protected Areas

- Port Phillip Heads Marine National Park

- Triconderoga Bay Dolphin Sanctuary Zone

Northern Port Phillip Bay

Some incredible marine environments can be found right on Melbourne’s doorstep, including coastal dunes, wetlands, highly productive seagrass meadows and unique drift algae beds. There are saltmarsh areas, mangrove stands and rocky reefs as well as three marine sanctuaries and a coastal park.

Saltmarsh areas at the Point Cook Coastal Park, west of Melbourne, are an important habitat for the endangered orange-bellied parrot (Neophema chrysogaster), as well as stabilising the shoreline, limiting flooding and helping improve water quality by trapping sediments and acting as a sink for pollutants. The wetland areas along the shoreline from Point Cooke to the mouth of Skeleton Creek provide an incredible diversity of habitats for marine organisms and important feeding grounds for fish and seabirds, including a nationally significant shorebird feeding area that extends between Altona and Williamstown.

The nearby Jawbone Marine Sanctuary at Williamstown supports diverse habitats including rocky reef, seagrass meadows, intertidal flats and saltmarsh. The largest surviving stand of mangroves in northern Port Phillip Bay occurs along a 200m section of this coast near Williamstown.

Subtidal sediments in Williamstown support many species and the basalt platform is a feeding and roosting site for migratory and waders and seabirds. The seagrass meadows are a nursery for juvenile fish and habitat for invertebrates. Because intertidal reef and coastal habitats at Williamstown have a long history of protection from direct human disturbance, unique intertidal population structures have developed over time.

Ricketts Point, at Beaumaris, is a marine sanctuary and home to a great diversity of habitats, making it an incredibly interesting area. There are rocky intertidal and subtidal reefs, sandy beaches, subtidal soft sediments, intertidal and subtidal seagrass meadows, algae-covered bommies, off-shore ledges and channels. An extensive area of shore platform extends over 150m seaward when exposed at low tide, supporting a high diversity of invertebrates. The offshore rocks and ledges attract fish too, including schools of southern hulafish (Trachinops caudimaculatus), and occasional wrasse and Victorian scalyfin (Parma victoriae). Cryptic weedfish and shrimp can be found amongst the algae.

The intertidal reef at Ricketts Point is an important feeding and roosting habitat for large numbers of seabirds and shorebirds, and has a high diversity of Port Phillip Bay invertebrates including abundant populations of bryozoans (sea mosses) and rare hydroids. The threatened snapping shrimp Athanopsis australis is also found at Beaumaris. Immediately to the east of Ricketts Point are the vertical cliffs of Table Rock Point. The area between Ricketts Point and Half Moon Bay (southeast of Sandringham) has shallow rocky reefs near the shore. Ricketts Point and Table Rock Point in Beaumaris also support small, isolated seagrass meadows.

There is a breeding colony of little penguins (Eudyptula minor) at St. Kilda, and pods of dolphins are a common site in the entire area. If you’re lucky, you may even spot the odd humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae).

Marine Protected Areas

- Point Cooke Marine Sanctuary

- Point Cooke Coastal Park

- Jawbone Marine Sanctuary

- Ricketts Point Marine Sanctuary

North Arm Westernport

North Arm Westernport is impressive for its different habitats right across the area. There are black and sulphurous mudflats, salt marsh habitat and mangroves, seagrass meadows, and deep underwater canyons and reefs. With each of these habitats providing a home or feeding ground to some diverse fauna, it is certainly an important marine region in Victoria.

Westernport to Melbourne’s south-east is Victoria’s second largest bay covering 680 square kilometres and containing two of Victoria’s largest islands, French and Phillip Islands. Westernport occupies part of a depression caused by faulting along the edges of the Bay, between the Mornington Peninsula to the West and the South Gippsland Highlands to the East. Erosion and deposition from runoff and rivers have altered the coastline over time. The depression has been submerged by marine waters, and the coastal and sea floor have been shaped by waves and currents.

Westerport is essentially a marine (rather than estuarine) inlet – as is Port Phillip. Today vast quantities of muddy sediment in and around the bay form shoals and marshlands. The mud (consisting of silt, clay and organic matter) is partly from river sediment washed into the bay, and partly the result of reworking by waves and tidal currents of fine-grained material derived from outcrops around and beneath the bay.

Westernport is subject to the maximum tidal range on the Victorian coast. The tides are the key to understanding Western Port’s marine life. As the oceans rise and fall with the moon, seawater is flushed in and out of bays like Western Port. These tidal currents take time to wind around the islands and there is quite a time lag between high tides at the mouth and head of the bay. Consequently, the difference in height between low and high tides is much greater than along the open coast and can reach over 3 m towards the north.

Because of the relatively sheltered waters of the open coast, mud has formed extensive layers across much of Western Port. These muds are generally black and have a strong sulphur smell, because little oxygen can penetrate them. More than 270 square kilometres of mud flats are exposed at low tide and other areas of the bay are very shallow. As water streams off these flats, it forms a network of channels in the soft mud. These channels gradually join to form larger channels that eventually drain into the deeper areas in the south. The mudflats of this area are nationally significant as feeding habitat for wader birds. They are also of State geomorphological significance.

Many small animals also live in the mud and seagrass beds. The mudflats support a wide diversity of deposit feeding animals including worms, and bivalve molluscs like pippies. These animals convert the debris that accumulates in the bay into animal tissue which is then available as food for animals like birds and fish. Fish gorge themselves on these animals and the birds feed on them all.

Over 65 % of Victoria’s birds have been sighted around the bay. Western Port is very important as a bird habitat, and over 295 species have been recorded in the area. These include large populations of black swans (Cygnus atratus), pied oystercatchers (Haematopus longirostris) and royal spoonbills (Platalea regia). Many of the migratory wader birds that spend summer in Victoria depend on Western Port because their main habitat requirements are mudflats for foraging and high tide roosts where birds wait for the next feeding period. Up to 15,000 wading birds and 10,000 black swans feed on the flats and seagrass meadows.

Westernport is recognised as one of the world’s most precious areas for wading birds, some of which migrate all the way to Siberia. These include the eastern curlew (Numenius madagascariensis), whose non-breeding birds migrate from north-eastern Asia, the bar-tailed godwit (Limosa lapponica) which breeds in Arctic regions of Eurasia and Alaska, and the curlew sandpiper (Calidris ferruginea), which breeds in the Arctic regions of eastern Siberia.

The French Island Marine National Park includes the waters around Barralier Island, which is a significant feeding habitat for the 32 species of migratory waders and one of the bay’s 13 high tide roosts. This habitat is particularly sensitive to disturbance. This island is an important high tide roost for birds, but due to its location on the very edge of the park it is not adequately protected.

Around the fringe of the bay are large areas of mangrove, saltmarsh and tea tree swamp. The North Arm of Western Port Bay contains significant and unique intertidal mudflats and channel habitats, as well as extensive seagrass beds, mangrove and saltmarsh. The area’s well developed tidal channel system of varying depth, profiles and orientations, contributes to the high diversity of habitats.

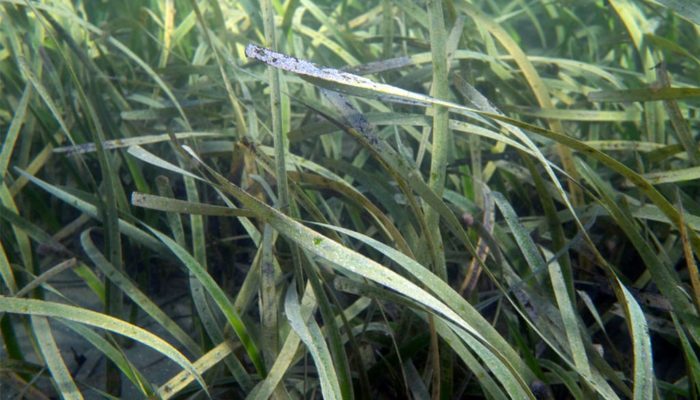

Extensive seagrass meadows are found in the area, including some areas where little loss of seagrass has been recorded. Seagrasses are extremely important habitats and play a major role as nursery areas for many fish species, including commercially and recreationally important species such as King George whiting (Sillaginodes punctata), bream and mullet. Seagrasses are extremely important habitats and play a major role as nursery areas for many fish species, including commercially and recreationally important species such as King George whiting (Sillaginodes punctata), bream and mullet. Seagrasses have disappeared from more than 80 per cent of Western Port during the 1970 and 1980’s. No single cause has been identified for this loss, but a reduction in the amount of light reaching the seagrass is often the culprit. This can be caused by an increase in the amount of sediment in the water, or from a bloom in the algae growing on the leaves, caused in turn by increased levels of sewerage or fertilisers entering the sea.

The northern shore of French Island has one of the most extensive areas of saltmarsh and mangrove communities in Victoria. These plants are unusual in that they can cope with the highly salty conditions of this environment. Mangroves are also able to cope with living in thick, airless mud. Mangroves are a vital part of the bay ecosystem and provide important habitat for numerous invertebrates including crustaceans (crabs, shrimp and sand hoppers), marine snails and bivalves, adult and juvenile fish. Unfortunately, these important habitats are not adequately protected by marine national parks or sanctuaries.

The most developed and extensive Victorian mangrove populations occur in Westernport Bay. White mangroves (Avicennia marina australasica) are the only mangroves that grow in Victoria and are actually flowering plants that have evolved strategies for surviving in a challenging environment. They can survive in very salty soils and mud by taking up salt through their roots and getting rid of it through specialised salt glands on the back of their leaves. They can grow in the thick airless mud because of a series of breathing roots that let them get oxygen directly from the air.

The mangroves are vital habitat for the life cycles of crabs, shrimps, sand hoppers, marine snails, and bivalves, and well as important feeding areas for adult and juvenile fish. Scavenging and filter-feeding animals do not eat the mangroves directly, however, mangrove leaves that fall into the water decompose to form detritus, which is a major food these animals in the Bay.

There are several islands in northern Westernport of State botanical and zoological significance. The relatively undisturbed mangrove and saltmarsh habitats of Watson Inlet and Quail Island are also of State significance as some of the most intact communities in Victoria.

Another important feature in northern Westernport is Crawfish Rock, which has deep reefs, pinnacles and canyons and underwater channels with extremely high conservation value. The marine community at Crawfish Rock is unique, with very high invertebrate diversity. A number of threatened species make their homes here. The area qualifies to be listed as a threatened community because of the unique and vulnerable nature of the marine community that it supports, which includes threatened hydroids.

Other rare species found in the area include threatened ghost shrimp (Michelea microphylla, Pseudocalliax tooradin), a threatened sea cucumber (Apsolidium handrecki), and a threatened snapping shrimp (Alpheus australosulcatus).

Marine Protected Areas

- Yaringa Marine National Park

- French Island Marine National Park

- Westernport Ramsar Site

Corner Inlet

There are many reasons why the marine environment at Corner Inlet is special. Tucked into the northern part of Wilsons Promontory, Corner Inlet is a forgotten gem of the Victorian coast. Its sheltered waters are almost completely surrounded by the granite hills of ‘the Prom’, the yellow dunes of Yanakie, the green rolling Strzelecki hills, and the low-lying islands of Nooramunga.

It is the most easterly, and consequently the warmest, of Victoria’s large bays. On a calm day the water develops an oily sheen, disturbed only by the occasional penguin, a diving cormorant, or a pod of dolphins. Corner Inlet supports huge numbers of migratory water birds and healthy populations of seafloor animals and plants that are rare or absent elsewhere in Victoria. It has a complex network of mangroves, saltmarsh, mud banks, seagrass beds, rocky islands and deeper channels.

On shallow mud banks, attractive seagrass meadows beckon beneath the surface waters. All four of Victoria’s embayment seagrasses form extensive beds here. Corner Inlet is the only place in Victoria where the broad-leaved seagrass (Posidonia australis) forms large meadows. Growing up to a metre in length, this seagrass is one of the world’s largest. Its beds are a very important habitat, stabilising the sediment and providing shelter and food for many other creatures including a range of large crabs, multicoloured seastars, sea snails, tiny iridescent squid and many fish from pipefish, stingarees, flathead, whiting and flounder.

The broad-leaved seagrass is also one of the most vulnerable species of seagrass. Once common right around Corner Inlet, large beds are now restricted to three banks towards the south. Seedlings are rare; instead the plant spreads across the mud banks via sub-surface roots. Posidonia seagrass beds have the poorest recovery rates of any coastal habitats known. For example, tracks made by vehicles over beds in South Australia’s Spencer Gulf in the 1910s are still clearly visible today. Sand ‘blow-outs’ are a regular feature of Posidonia beds and may persist for decades.

Marine Protected Areas

- Corner Inlet Marine National Park

- Corner Inlet Ramsar Site

- Corner Inlet Marine and Coastal Park

- Nooramunga Marine and Coastal Park