PARK WATCH Article September 2024 |

Shannon Hurley, Nature Conservation Campaigner, on the ecological costs we can’t overlook in the race to reach renewable energy technologies

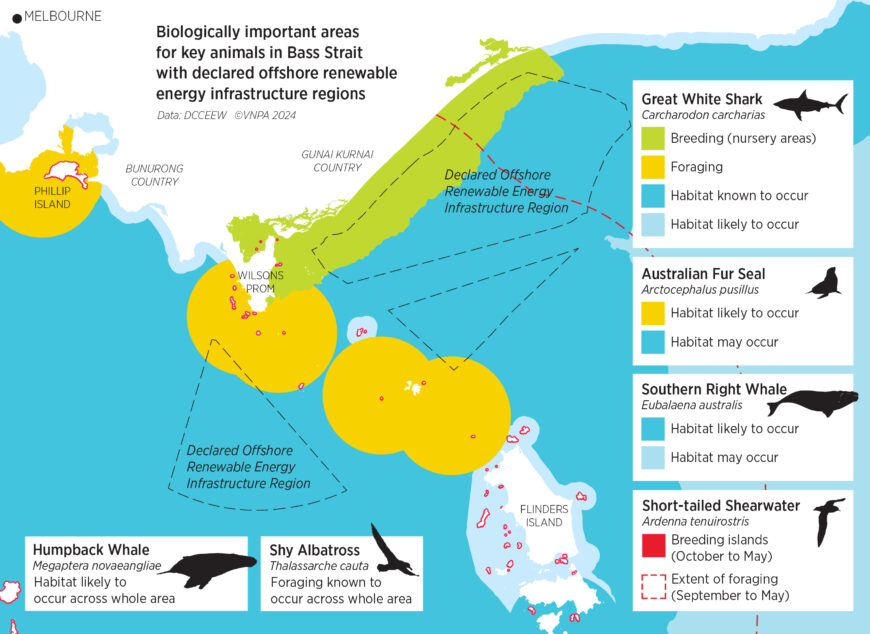

Victoria’s south-eastern seas and shores are unusually abundant. Some 80 per cent of the marine life occurs nowhere else on our blue planet. Gippsland’s waters and coast are no exception. Sponge-lined caves in Wilsons Promontory, a fur seal colony, offshore islands busy with seabirds feeding and breeding, and a Great White Shark nursery, to name a few.

The sandy plains of Gippsland may look devoid of life but don’t be fooled. They’re thought to have one of the highest diversities of life on Earth, with 860 species discovered within ten square metres! Sand-dwelling wildlife include tube building worms, small molluscs and many tiny crustaceans.

Many of these marine wildlife and habitats face large-scale, multi project, cumulative impacts from the construction and ongoing operation of wind farms. The six project licenses granted so far in the Gippsland Offshore Wind Farm Zone open the flood gates for even larger repercussions. This is especially true where rare habitats and migratory threatened wildlife are concerned.

If we put offshore wind and protecting marine life on the same page, we’ll achieve the best outcomes through creating intelligent and nature-safe planning.

Our raising of these concerns is not to shut down the offshore renewables transition (as would appear to be the case from the anti-wind farm lobby), but to call for better planning decisions.

Unfortunately, the ship has already sailed for highlighting marine hotspots before declaring the Gippsland Offshore Wind Farm Zone. But it’s not too late to work towards coordinating planning decisions within it. Baseline knowledge, habitat mapping and species sensitivity mapping is crucial to inform and lead better planning decisions.

Offshore ocean environments are often out of sight, but they shouldn’t be out of mind. It’s well-known that avoiding potential negative impacts is the easiest, cheapest, and most effective strategy. Waiting to address these impacts with mitigation measures later is often too late for marine wildlife.

We can see the consequences of poorly managed nature-safe transitions in other parts of the world. For example, in France, wind turbines had to be dismantled because strategic planning failed to account for their impact on eagles.

To prevent delays in establishing nature-safe offshore wind farms, VNPA is calling for the following strategic marine planning steps:

1. Marine research. A government-led framework to build knowledge and data on marine ecosystem values, so areas with higher biodiversity are identified and avoided, including:

- Data inventory and analysis of data gaps and needs (ecosystem and individual species).

- Information and data collected by developers be stored in government portals and made available for strategic planning purposes.

- Habitat mapping and baseline studies on abundance, distribution and behaviour of priority/high risk species.

- Regional-scale biodiversity sensitivity mapping for priority species, habitats, and high-value areas such as marine national parks.

2. Advisory body to consult on impacts of the energy transition on nature (including marine issues).

3. Strategic marine planning, such as marine spatial planning, should be used to identify no-go areas in federal and state waters to protect high-value marine biodiversity. Similarly, priority development areas should be identified in regions with lower biodiversity sensitivity.

Impacts on marine life

Let’s take a closer look at what flies above and lies beneath Gippsland’s waters, potential impacts on them and the role of regional-scale strategic planning.

The most obvious negative impacts are direct collision with marine life, like seabirds, and harm to seafloor habitat. Baseline studies, habitat and biodiversity-sensitivity mapping for species like birds, where data is available, are crucial for a nature-safe energy transition.

A taste of the work so far

A statewide DEECA analysis using available data identified 144 species relevant to the Gippsland offshore wind farm zone (known as planning areas 6 and 7 in the marine spatial planning guidelines). Of those 144 species, 51 are listed under state nature laws and 121 under national nature laws.

At a federal level, the National Environmental Science Program (NESP) is creating an inventory of existing environmental and cultural data on distributions of priority species, like Southern Right Whales (Eubalaena australis)/Koontapool for the Gunditjmara. It’s unclear how this research will inform the planning of offshore wind in high value biodiversity areas.

There’s also work being undertaken by developers like Southerly Ten (formerly Star of the South) and others as they prepare environmental assessments.

Marine values of Gippsland

Seabirds

The waters of southern Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand are global hot spots for albatross, petrels, shearwaters and Storm Petrels. Around half of the world’s pelagic species occur in the region, including 17 of the worlds 22 albatross species. Areas off Victoria are national seabird ‘hotspots’ with many seabirds foraging in these areas. Offshore wind generation poses significant impact on birds due to direct collision, displacement from preferred habitat, and alteration of flight paths.

There are two main ways bird collision strike on turbines is reduced – avoid siting them in direct flight paths or near feeding/breeding areas, and curtailment (reducing turbine speed) to avoid collisions.

Over 246 bird taxa have been identified in Bass Strait, 80 of which are high risk. These include Critically Endangered migratory shorebirds, albatrosses and migratory parrots that cross Bass Strait, as well as range-restricted endemic coastal nesting birds. Albatross such as the Black-browed, Shy, Wandering and Grey-headed; Swift and Orange-bellied Parrots, Curlew Sandpiper and the Sooty Shearwater are at high-risk.

Fish and sharks

Many important fish and sharks live within the project area, which also hosts a Great White Shark nursery ground.

Globally, there is very little research on the impact on our scaley friends from offshore development. Over 30 fish have been identified in the project area including the Blue Warehou, Australian Grayling, King George Whiting, School Shark and Southern Bluefin Tuna.

Marine mammals

Marine mammals, including whales and dolphins, are particularly susceptible to the negative impacts of offshore wind farms. The impact level is dependent on the individual species. Underwater noise from construction phase (i.e. pile driving) is of most concern and is likely to cause hearing impairment at close range, with impacts felt kilometres away. Behaviour changes, like migration away from the physical presence of turbines and vessel strikes, must also be considered.

Over ten species have been identified in the area. Those of high concern include Southern Right, Blue and Humpback whales, Australian Fur Seals and Short-beaked Common Dolphins.

Habitats of Gippsland

In state waters, habitat types have been classified on a range of levels, down to ‘sub-biotopes’, the finest scale. In Gippsland there are 20 distinct habitats, meaning there is a diversity of valuable marine ecosystems that many animals depend on.

Although some surveys and mapping have been conducted in federal waters where offshore wind farms will be located, additional work within specific offshore zones is vital.

It’s the obvious and responsible way to make sure our decisions are nature-safe and marine life can thrive.

Find out more in the Winds of change discussion paper.

- Read the latest full edition of Park Watch magazine

- Subscribe to keep up-to-date about this and other nature issues in Victoria

- Become a member to receive Park Watch magazine in print