PARK WATCH Article November 2022 |

Once abundant in Victorian waters, Giant Kelp are now threatened. Kade Mills and Consuelo Quevedo report on plans to record oral histories to help protect, preserve and even restore these giant forests of the sea.

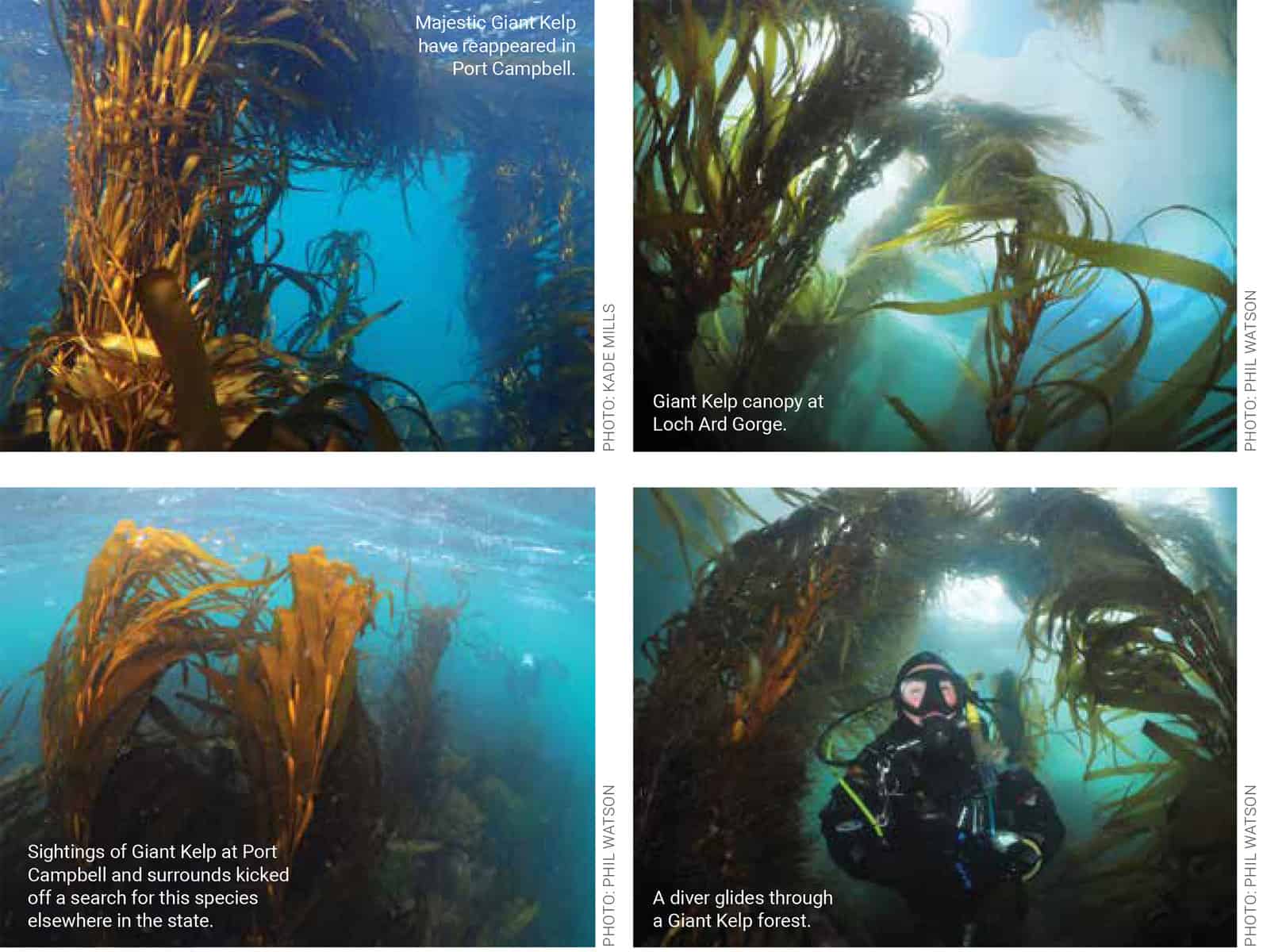

Floating above a forest of Giant Kelp evokes a clear understanding of the phrase ‘birds eye view’. Giant Kelp or String Kelp (Macrocystis pyrifera) is the largest seaweed in our oceans, growing at a rate of up to half a metre a day as it reaches for the surface from depths of up to 30 metres. At the surface it continues to grow horizontally, floating in large mats that form an enormous canopy akin to terrestrial forests. Snorkelling among the canopy you will share the space with a diverse array of fish and as you dive towards the bottom you encounter crayfish, abalone and maybe even a Weedy Seadragon hiding among the fronds.

Diving among Giant Kelp forests was a common occurrence in Victoria during the 20th century. In fact, many divers recall having to carry a knife with them in case they became entangled in the forest and had to cut themselves free. Prior to this, early maps of the Victorian coast demarcate large swathes of Giant Kelp unsuitable for ships’ passage. Ongoing work by Deakin University into Aboriginal uses of seaweeds tells us there is much more to be learnt about historical distribution of seaweeds and Giant Kelp in particular.

We no longer find Giant Kelp at many places it was commonly encountered – and it seems even this fact has been overlooked. Maybe it’s generational amnesia – the idea that fundamental matters are lost unnoticed and the concept of ‘nature’ changes with each generation, or maybe it’s that until recently seaweeds, and the role they play in our coastal systems, has long been ignored.

Giant Kelp forests once abundant throughout temperate regions in the southern hemisphere and along the west coast of North America are slowly disappearing. They face threats from climate change (rising ocean temperatures, range extension of prey animals and increased storm activity) but they may also hold part of the answer to climate change with their ability to grow quickly and sequester carbon. Add to this their ability in minimising coastal erosion and preventing coastal storm damage by reducing wave energy by up to 70 per cent, we have a powerful ally in minimising climate change and its associated impacts.

While work is currently underway to restore Giant Kelp forests in Tasmania, our forests in Victoria have largely been forgotten. That is until Giant Kelp started reappearing in Port Campbell harbour recently. These sightings triggered discussions among ‘old timers’ about the days when Giant Kelp was so abundant as to be a nuisance in some places, which further triggered a search for records on Giant Kelp distribution in the state. It was during this search that it was realised the records we do have are limited, dispersed throughout maps, books and quite often people’s memories.

That’s why we’re working together with members of the public and various agencies to document and distil the oral histories of experienced people into something that can be used to help protect, preserve and restore the giant forests of the sea.

You can log your Giant Kelp sightings along the Victorian coastline in the iNaturalist project ‘Mission Macrocystis’ (www.inaturalist.org/projects/mission-macrocystis) and follow their Facebook page for updates www.facebook.com/MissionMacrocystis.

Image: Kade Mills

Did you like reading this article? You can read the latest full edition of Park Watch magazine online.

Want to be kept up to date about this and other nature issues in Victoria? Subscribe to our email updates.

You can also receive our print magazine Park Watch four times a year by becoming a member. Find out more.