PARK WATCH Article December 2023 |

Professor Sarah Bekessy leads the ICON Science research group at RMIT University which uses interdisciplinary approaches to solve complex biodiversity conservation problems. The following is an extract from her marvellous presentation at VNPA’s 71st Annual General Meeting on 24 October 2023

At my son’s school, Carlton North Primary School, we were very lucky to have the expertise and knowledge of Uncle Dave Wandin, an extraordinary and remarkable Wurundjeri elder, who worked with our school to bestow a totem species on the school. The kids learnt about the significance of totems. They learnt how to care for and create habitat for the species – a plant, Matted Flax-lily (Dianella amoena), a native grassland species considered endemic to Victoria. We planted a large population of Matted Flax-lily on the school grounds, one of the biggest populations in existence.

The kids learnt about the science of conservation, about the remarkable depth and value of Indigenous science and how it can go hand-in-hand with western science to solve some of our major societal challenges. They learnt about how to see how the school is part of the landscape, where the Matted Flax-lily can be a place where the Blue-banded Bees can come from the creek to the school.

The school is now cooler with more vegetation; more resilient to extreme weather events and has better learning places. We know that kids playing in more biodiverse places in schools have improved cognitive development and lower incidence of behavioural issues like ADHD. The most important thing they learnt, is if they care for that totem, and nature in general, it will care for them.

Nature is cool!

Nature in the city allows every person the opportunity to see, in their everyday lives, how they thrive when nature thrives. We’re facing the exponential growth of our cities, and extreme events like the 47 degree day we saw on Black Saturday. It has us thinking how we can create cities that are resilient and can help keep people healthy and happy and connected in these places. People around the world are looking more to nature to be a key part of the solution to some of these problems.

We know the benefits of nature cities are extraordinary, such as improving health, promoting sense of community and social interaction, improved cognitive functioning in children, enhancing self-discipline and reducing aggressive behaviour and crime.

The fact is that we can lower the temperature of the city by 8ºC during a heat wave. We can clean our water and make sure the beautiful Yarra River/Birrarung has a chance to thrive even when having an unprecedented dump of rain. Our physical and mental wellbeing is so much enhanced by having regular contact with nature. If you live in a street with more nature, you will have a lower incidence of diabetes, cancer and heart disease. You’ll sleep better and you’ll probably have better social connections.

Cities with more biodiversity are also able to be part of the solution. Our gardens, streetscapes and parks can be places where threatened species can be given a haven. They’re a critical opportunity for engaging with Aboriginal culture.

City critters

Some creatures completely rely on cities. And sometimes we change cities to make them more suited to creatures, for example, the Flying Foxes in Melbourne.

A new study from Adelaide University has found that reintroducing a diverse array of native plants to public spaces can help strengthen people’s immune systems by exposing them to beneficial microbes. Biodiverse natural environments help prevent illnesses like allergies and asthma, improve mental and physical health, as well as generate employment.

Planning for nature

We need to think less concrete, more vegetation. There are so many opportunities, and not just boring Plane Trees. You can fill a city with trees but have little net benefit to biodiversity if you fail to think about the stuff that belongs there that can really deliver structural diversity – the understorey, midstorey and the overstorey.

In Adelaide, they have legislated for our protocol of Biodiversity Sensitive Urban Design and they’re doing really well at implementing this in streetscapes.

It’s about diversity. There’s a common brown butterfly that once used to emerge in big numbers at the start of one of the seven Wurundjeri seasons. We’re trying to encourage the planting of habitat that will attract a return of these butterflies – and connect us to Wurundjeri culture and seasons.

Unfortunately, a lot of our development in Melbourne has not been compatible with the vision I’m painting of people having access to everyday to nature. We have urban fringe monstrosities, inner city high rise and middle ring knock down–rebuilds, where we lose a lot of vegetation for not much gain of how many people we fit in to the suburb. It’s about money-making. We need to rethink the way we are developing our cities in Australia – in a way that allows people and nature to thrive.

Our planning system is stuck in a way of thinking that nature is a problem to be dealt. The planning system has biodiversity constraint layers. We should be trying to maximise nature at every point of the planning process. And not ‘off-setting’ I hate this idea that we can clear some nature, and plant somewhere else to ‘offset’ it.

We don’t have a planning system that adequately respects biodiversity in cities. Recently in Campbellfield, a developer cleared the last remnant of Red Gum grassy woodland and was fined $200,000. They subsequently went to VCAT and got the green light to proceed with a $7 million development!

Fixing the future

The 2022 UN Biodiversity Conference, COP15 in Montreal, created Target 12 to put nature back into cities. At RMIT, our Biodiversity Sensitive Urban Design protocol is a systematic and scientifically driven approach to bringing back nature into cities.

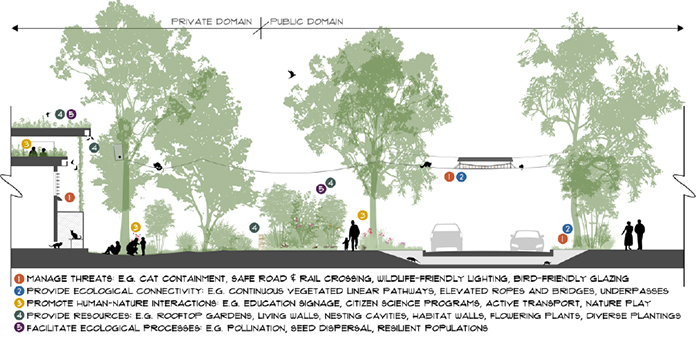

We are working with designers, developers and government agencies across Australia to implement Biodiversity Sensitive Urban Design. It starts with setting clear objectives for species and ecosystems then requires innovative designs to deliver resources, minimise threats and generate ecological connectivity for those species. Ideas include planting native ground covers, improving midstorey verge vegetation, passive irrigation beds and nature-friendly retaining walls – where lizards can thrive. There’s a type of brick where birds can nest on one side, and we can watch them from the other! We can make cities less inhospitable to nature, for example: building catios (containing domestic cats); having windows tilting downwards to stop birds flying into them; and lighting that is the right spectrum, so it doesn’t bother wildlife.

We can increase connectivity by creating streetscapes and paths that connect you to parks and rivers; and wildlife gardening programs – planting in a way that helps native animals thrive and ways that encourage people to want to be nature-positive stewards.

My vision is that all this is possible, do-able and really desirable. We can bring nature back, allow it to thrive in our cities and at the same time create places where people are going to be healthier, happier and more connected with nature and more connected with each other – it’s an altogether enchanting vision.

- Read the latest full edition of Park Watch magazine

- Subscribe to keep up-to-date about this and other nature issues in Victoria

- Become a member to receive Park Watch magazine in print