PARK WATCH June 2019 |

Parks Victoria’s well-considered Draft Barmah Wetland Strategy outclasses the Environment and Resources Departments’ non-committal Draft Deer Strategy by a mile, says VNPA Parks Protection Campaigner Phil Ingamells.

We live in challenging times for nature. Ecological systems are pretty much in decline worldwide, and the resources to manage them are rarely adequate.

But our knowledge of native species, and how natural systems work, is growing at a great rate.

That puts those who frame land management plans and strategies in a really important space. But it’s also a tricky space.

They must honour legislative imperatives to maintain species and ecological processes, especially within our national parks and reserves; yet they feel obliged to respond to perceived ‘stakeholder’ expectations. And then there’s an overlying obligation to answer to their political masters and deliver miracles with inadequate resources.

It would, of course, be sensible to have a standard format and set of criteria for land management plans and strategies. But those responsible for developing plans are faced with a stormy sea of options, confusingly ranging from the vague and non-committal to the enlightened and practical.

If there was to be a standard in the future (and there should be) Parks Victoria’s draft strategy for protecting Barmah National Park’s Ramsar-listed flood plain marshes is a very good model.

The Barmah Wetland Strategic Action Plan

Victoria, though a small Australian state, houses a remarkably diverse range of habitat types, and the Barmah flood plains are among the most interesting of them. Traditionally inundated when snowmelt water from the high country reached a narrow point in the Murray (the ‘Barmah choke’), the extensive wetlands support large breeding populations of native waterbirds, fish, turtles, frogs and reptiles.

Barmah National Park has been justifiably called Victoria’s Kakadu, but in recent decades the increasingly complex regulation of flows in the Murray River, starting with the construction of the Hume Weir, have confounded plans to maintain the timing and extent of floodwaters. Damaging late summer flows are now the norm.

Most remarkable of the several types of Barmah wetland is the moira grass plains, and Barmah is, or was, by far the most significant site for this type of wetland in the whole Murray Darling Basin.

In the 1930s, decades before Barmah was added to the Ramsar listing of internationally important wetland sites, there were a mighty 4,000 hectares of moira grass. By 1979, at the time of listing, around 1650 hectares remained. According to Parks Victoria’s draft strategy, that area had decreased to 182 hectares by 2015 – about five per cent of the 1930 extent. It could disappear completely by 2026, and the unnatural summer flooding is one of the main culprits.

Flooding isn’t the whole problem. Feral horses (and before the park was proclaimed, cattle) have been trashing the wetlands for decades, and there are weed invasions.

Importantly, the Murray Darling Basin’s Water Regulator is unlikely to mandate better environmental flows to Barmah unless Victoria also addresses the other impacts on the wetlands, such horses, pigs, goats and deer, invasive weeds and other threats.

Parks Victoria’s draft Strategic Action Plan for the wetlands is an evidence-based document, that addresses all of the threats, and sets deliverable targets. And it is securely founded within the context of Victoria’s National Parks Act 1975, the Ramsar listing, and the listing of feral horses as a threatening process.

Feral horse management is both the most pressing and the most publicly difficult part of the plan to execute. But Parks Victoria has researched the history of the horses (they’re a mixed breed dating largely from the 1950s), established the current size of the population (around 800), and identified the damage they cause (widespread and considerable, to both environmental and cultural sites).

The feral horse population will be reduced to around

100 horses over the three year period, by either rehoming or euthanasing on site, with complete removal mandated after that period. The VNPA would prefer complete removal within the three years (or straight away!), but at least a horse-free Barmah is the eventual goal of the strategy.

By comparison, last year’s draft deer management strategy, produced jointly by Victoria’s agriculture and environment departments, was not a draft to be emulated.

Victoria’s Deer Management Strategy

You might expect that government departments empowered to enact Victoria’s environmental laws would come up with a strategy that responded to those imperatives, but last year’s draft deer strategy didn’t come close. Indeed its lack of ambition was reflected in such aims as “maximising the positives that can be gained from their presence”.

That was an odd call, given deer are trashing Victoria’s protected areas and listed threatened species from the Mallee to the East Gippsland coast, from the Murray to the Otways. They are having a devastating impact on Victoria’s rainforests, our recovering alpine regions, and on hard won and costly revegetation programs across the state.

They are also impacting vineyards, orchards, farms and suburban gardens, and creating a growing hazard on our roads.

VNPA, after consulting a number of well-qualified ecologists and others concerned with the deer population explosion in the state, compiled an open letter to three Victorian ministers variously responsible for aspects of the draft: Ministers Jaclyn Symes (agriculture), Lily D’Ambrosio (environment), and Lisa Neville (water).

The letter was signed by over 90 Landcare, agriculture and environment groups, leading ecologists and a range of other affected organisations from across Victoria. It called for a much strengthened final strategy.

It asked for many things that were not adequately, or at all, addressed in the draft, including (but not only):

- Listing all deer as pest species, in line with state and federal environmental law.

- Setting up a statewide zoning system that prioritised deer control in national parks, other protected areas, and for listed threatened species and communities.

- Removing the draft’s notion that some areas should protect deer as a hunting resource.

- Setting evidence-based targets for effective control of deer.

- Allocating adequate recurrent funding for pest control operations on public land.

- Expanding the engagement of professional pest control operators.

- Expanding Parks Victoria’s programs using accredited recreational shooters in targeted programs.

- Working collaboratively with other states and the federal government.

- Resourcing a deer-specific targeted baiting strategy for the state.

- Supporting research into new control methods.

- Increasing penalties for illegal hunting, and for translocating live deer.

We accept that deer management is difficult, and that the compromises in the draft were largely the result of pressure from interest groups. However, we believe (and certainly hope) that the final strategy will be a much-changed document. It’s unfortunate, though, that a more practical and ambitious draft wasn’t available for public comment.

And it’s unfortunate that the development of such important documents don’t have well-established, clear criteria that they should meet. Both our land management agencies, and the areas they manage, would be much better places if they did.

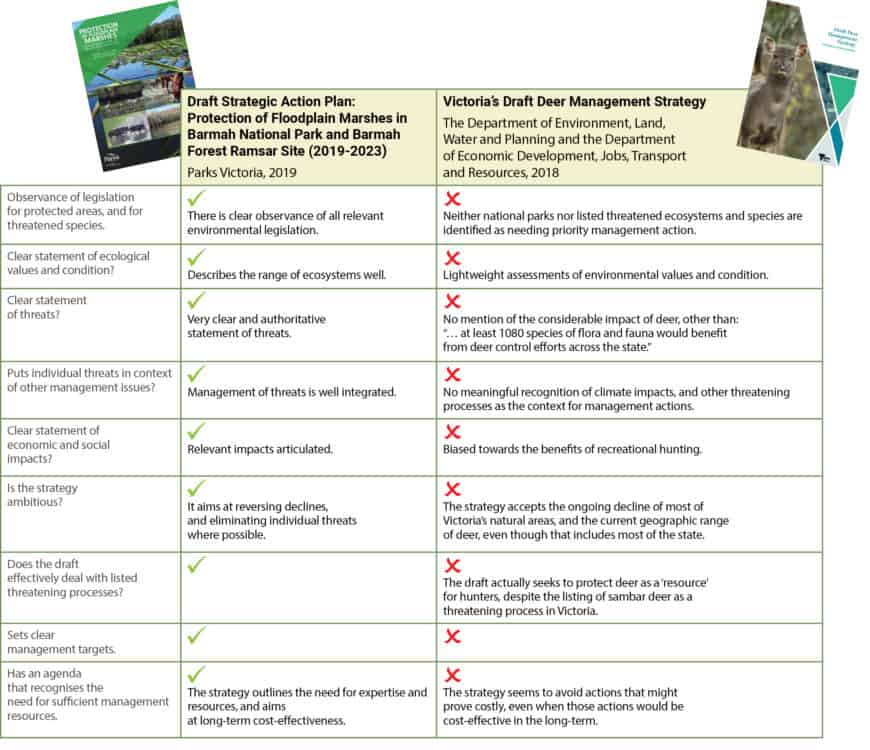

The following table compares the two recent drafts:

Public comment on both drafts has closed.

Did you like reading this article? Want to be kept up to date about this and other nature issues in Victoria? Subscribe to our email updates.

You can also receive our print magazine Park Watch four times a year by becoming a member. Find out more here.