PARK WATCH September 2024 |

Jessie Borrelle, Digital Engagement & Communications Manager, on celebrating our own Golden Globes

You don’t need to look for wattles after July, they’ll find you. To take a walk in early Spring is to witness a slow-motion fireworks display. It’s as if, after being dimmed for months, the lights in the bush have been turned back on.

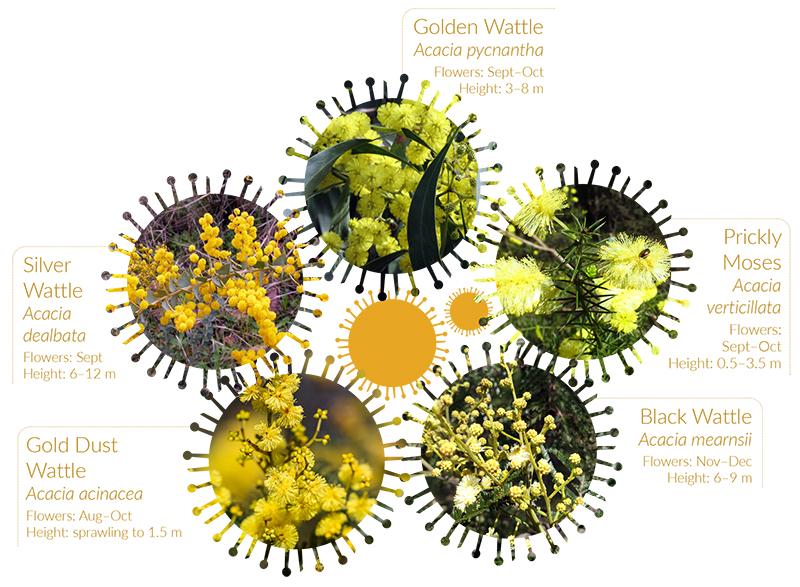

There are some 90 species native to Victoria and they vary greatly, in kind and in habit. Some loom large (Acacia mearnsii) and others crouch close to the earth (Acacia verticillata). Many burn bright and quick, like Golden Wattle (Acacia pyncantha), here for a good time, not a long time. Not the likes of Acacia melanoxylon, these Blackwoods reach heights of 15 metres and frequently witness ten decades.

Silver Wattle/Muyan (Acacia dealbata) and other species are significant in Wurundjeri culture, whose resourcefulness knows no bounds. Pods for soap, seeds for flour, foliage for medicine, bark for bandages, wood for fuel, instruments and weapons. Settlers lent the genus acacia the name wattle after the ‘wattle and daub’ building technique of assembled sticks, earth, and clay.

Pops of gold, bursts of yellow, their flowers bursting banana-bright. I have to remind myself that this visual feast isn’t for me, but a smorgasbord of leaf, flower and seed for hungry birds, beetles and bugs. These native legumes have been served season after season for millions of years. Australian acacia pollen fossils can be traced back to the Oligocene – an epoch 25 million years old.

Acacia pollen has heft. Once wattle pollen departs the flower it can’t move far at all, often hitching a ride in the feathers of birds. Despite this, it’s often unfairly accused of triggering runny noses and swollen eyes. (The culprit is more likely grass pollen, light and wind-borne).

Wattles are incredibly influential in their communities. They regenerate fast – a talent instrumental in restoring the nitrogen balance of soils after fire. Wattles devour the copious beams of light and offer safe harbour for slow moving plants.

They lure in silvereyes, honeyeaters and thornbills with a sugary fluid expressed during flowering. Red-tailed Black Cockatoos, Gang Gangs, Emus, Superb Fairy-wrens and Brush Bronzewings all feed on their seeds. They’re sometimes used as an indicator of the presence of Leadbeater’s Possum, who seek out the carbohydrate-rich sap of acacias in the Central Highlands. This is only a small glimpse into their complex contributions to the living web of nature.

The more I learn about wattles, the more I am hypnotised by these blooming beauties.

If you’re keen to go deeper into your wattle journey, I recommend the classic Field Guide to Victorian Wattles by FJC Rogers, illustrations by John Truscott. Each species is expertly illustrated, with scientific and common names, occurrence, flowering, appearance and size. Published in 1978, it may be an oldie, but (if you can get hold of it) it sure is a goodie!

- Subscribe to keep up-to-date about this and other nature issues in Victoria

- Become a member to receive Park Watch magazine in print