PARK WATCH Article December 2021 |

Executive Director Matt Ruchel says it is time to stop the decline and start recovery.

According to the United Nations, nature-based solutions offer the best way to achieve human well-being, tackle climate change, and protect our living planet. Yet globally, nature is in crisis, as we are losing species at a rate 1000 times greater than at any other time in recorded human history, and one million species face extinction.

Victoria is a microcosm of this global trend. We now have almost 2000 species on our official threatened species list, of which 28 per cent are now listed as critically endangered, the last step toward extinction in the wild. We are in an extinction crisis.

Victoria also prides itself on being a progressive and prosperous state. But our state is responsible for over half of all wildlife extinctions in Australia. While we have been leaders in nature conservation in the past, bold action is needed if we are to regain this status.

Australia has joined the High Ambition Coalition (HAC) for Nature and People, an intergovernmental group of 70 countries with the central goal of protecting at least 30 per cent of the world’s land and ocean by 2030. While these goals don’t always translate to subnational governments, like the state of Victoria, as we have seen with the efforts to reduce carbon emissions, state and territory governments can be key drivers of change.

The last comprehensive election policy for nature in Victoria was in 2014. Labor’s election announcement ‘Our Environment Our Future’ claimed that it would “work in partnership … to put the care and protection of our environment back on the agenda”.

The Andrews Government committed to a series of significant reforms including a new Marine and Coastal Act, a new Yarra River Act, important programs for riparian land, review of native vegetation regulations, a review of the Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act, and importantly, an update of statewide biodiversity strategy.

The Andrews Government released the Protecting Victoria’s Environment – Biodiversity 2037 strategy in 2017. While far from perfect, its goal of “Victoria’s natural environment is healthy” and targeting “a net improvement in the outlook across all species by 2037” was pragmatic – and at least it was a strategy.

In October this year, the Victorian Auditor- General’s Office released a highly critical report Protecting Victoria’s Biodiversity, the first such review of the strategy. Its findings were scathing. It is clear from the report that current management efforts and funding allocations are not meeting the objectives of the Biodiversity 2037 strategy nor the Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 (FFG Act) to address the extinction crisis and to stop the decline of threatened species.

Some of the findings of the report are alarming, but sadly not surprising, including that the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP):

- cannot demonstrate if, or how well, it is halting further decline in Victoria’s threatened species populations.

- cannot guarantee the protection of all threatened species, given current funding levels.

- continues to make limited use of available legislative tools to protect threatened species.

- has no transparent, risk-based process to prioritise these species for management.

- data used in the various models is old and likely outdated, and has some critical gaps.

- lacks performance indicators and reporting to demonstrate the impact of its management interventions on halting the decline of threatened species.

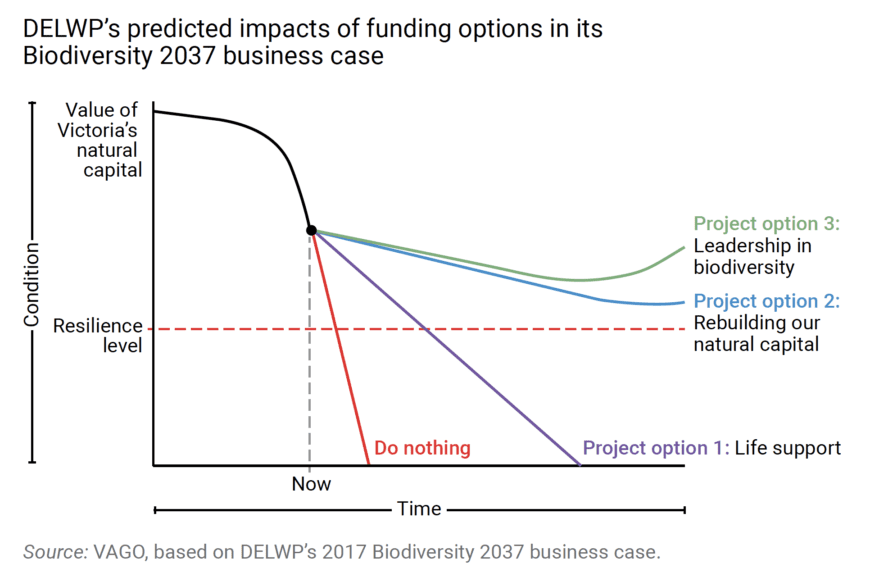

Critically, funding available to DELWP to protect biodiversity falls significantly short of what is needed. According to the Auditor- General’s report, in 2017, DELWP received $86.3 million (project option 1, see graph below) in government funding over four years to implement Biodiversity 2037 – less than half what it requested. The government also projected DELWP would receive $20 million per annum after 2021 for Biodiversity 2037’s ongoing implementation – approximately a third of what was requested.

DELWP’S unsuccessful funding bid for $269 million over four years (about $67 million per annum) was relatively small and very achievable in the scheme of things – only the cost of two level-crossing removals, for example.

The Auditor-General’s report also notes that since 2017, DELWP has not provided further advice to the government about the impacts of the funding received compared to other funding project options provided in the Biodiversity 2037 business case (see graph above). It has also not provided updated impacts of funding levels and costings given the increased number of species now listed as threatened under the FFG Act.

While the 2014 election commitments and 2017 strategy provided some hope, there was little follow-through at the 2018 election, with very few conservation-related initiatives. Policy was confined to the ‘Victoria’s Great Outdoors’ program, a nature-based extension of the ‘Victoria’s Big Build’ philosophy. While it came with a $100 million plus price tag, it was largely infrastructure-focused with commitments to cheaper camping fees, new campgrounds, 4WD tracks and walking trails.

This isn’t just the result of a lack of up-to-date knowledge, policies and programs. It’s also a refusal to actually use the existing legislative tools, commit the required funding, and follow through with action. Frankly speaking, the avoidable decline of our unique plants, animals and landscapes isn’t an accident; it’s neglect.

The Auditor-General’s report is sobering, but it is also a wake-up call for the opportunities Victoria has to invest in threatened species’ recovery to set our unique biodiversity up for success.

The Biodiversity 2037 strategy and the FFG Act do provide decent frameworks and objectives – we just desperately need more resourcing and focus for their implementation.

Without it, we will not reverse this distressing decline in our unique native plants and animals. Protecting habitat could be a key avenue to help threatened species, including on both private and public land and creating new national parks, as well as the important job of properly managing these areas once protected.

Increased investment in threatened species recovery will bring real and lasting benefits for Victoria’s irreplaceable natural heritage, and will also be good for tourism and regional economy and jobs.

A good starting point would be for commitments to be made as we move into another election year to halt the decline and instead move towards the restoration of our biodiversity. This would involve:

- A dedicated long-term threatened species program for Victoria, of at least $500 million which will:

• Take all available actions under state threatened species laws to protect species in decline (including using laws to protect critical habitats)

• Improve prioritisation of threatened species for protection

• Enable enhanced and targeted landscape programs to control key threats statewide including feral animals and pests to facilitate recovery - Dramatic increase in public funding for land and sea conservation and threatened species programs including:

• Increase in funding core ecological management funding for Parks Victoria to at least one per cent of state expenditure annually

• Increase targeted funding for Community Action, Landcare and private land protection

• Expanded Traditional Owner joint management on Country

• An enhanced threatened species recovery and action program across all publicly-owned land and sea

• Dramatically speed up the transition out of native forest logging - New $30–$50 million for a Land Conservation Revolving fund which “purchase, protect, resells” high conservation private land to be run by the Trust for Nature.

- Strengthen the Wildlife Act to properly protect all native species.

Did you like reading this article? You can read the latest full edition of Park Watch magazine online here.

Want to be kept up to date about this and other nature issues in Victoria? Subscribe to our email updates.

You can also receive our print magazine Park Watch four times a year by becoming a member. Find out more here.