PARK WATCH Article November 2022 |

Don Garden has compiled an extensive history of VNPA. This is a brief summary, covering the years 1952 to 2010.

Crosbie Morrison and the formation of the Victorian National Parks Association

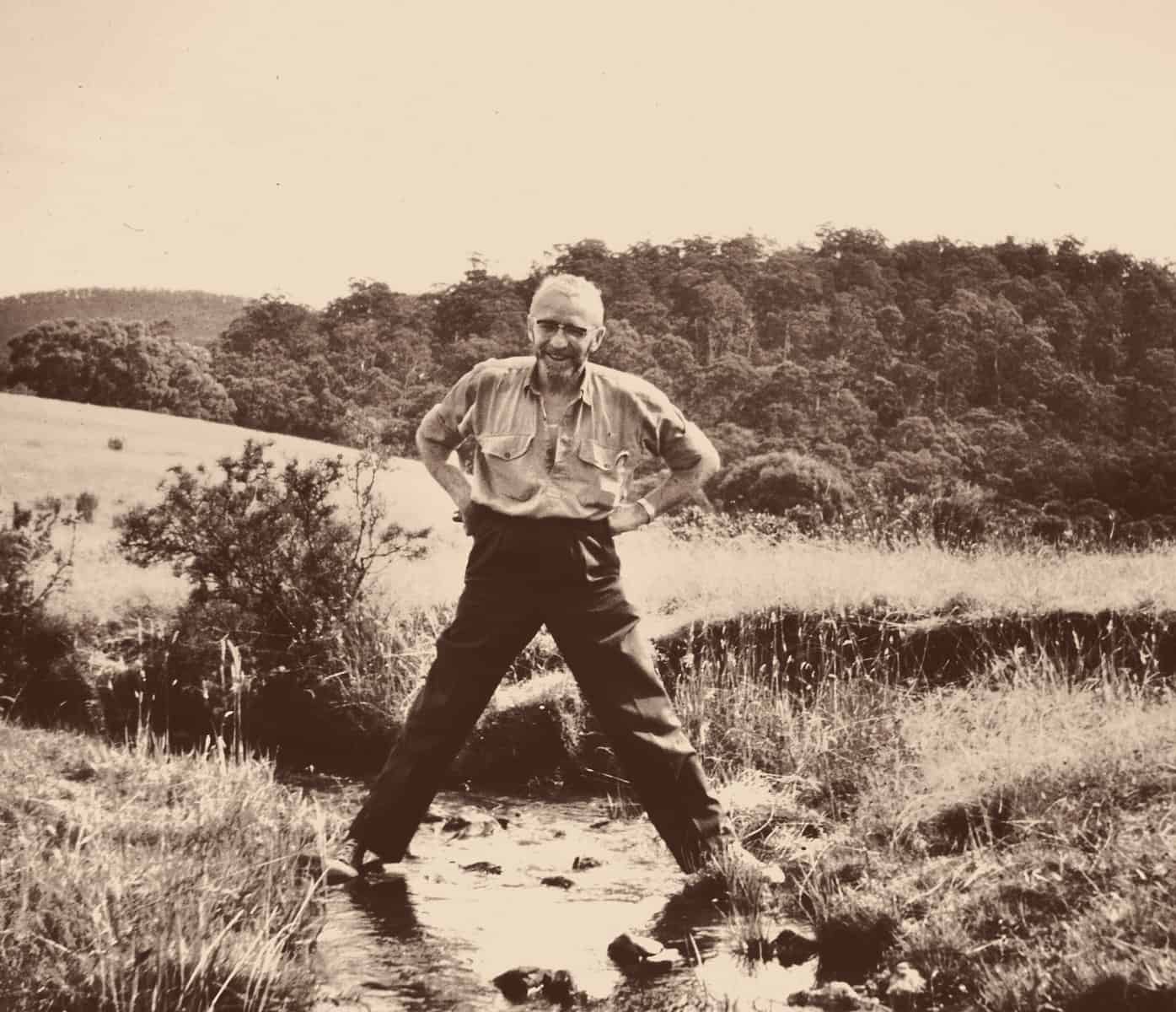

Many people were involved in the formation of VNPA in 1952, but the most important public figure was Philip Crosbie Morrison (1900–1958).

To read Crosbie Morrison’s biography by Graham Pizzey is to be almost overwhelmed by his activities and achievements: a keen amateur naturalist, zoologist, journalist, founder of natural history and conservation magazine Wild Life, a radio broadcaster and popular public speaker.

The steady loss of flora and fauna in Victoria, under pressure from agriculture, development and 70 years of the Victorian National Parks Association introduced pests, was a profound source of concern for Morrison and other conservationists in the middle of the 20th century. Even the so-called ‘national parks’ were in severe decline from inadequate legislative protection, poor administration and no government funding.

Wilsons Promontory National Park was seriously degraded by military use during WWII and by fire and rabbits, while across Victoria park management committees (where they existed) resorted to leasing parks for grazing, timber cutting and quarrying in order to raise revenue.

In 1946 Morrison called for a ‘New Deal’ for the parks and reserves. Between 1946 and 1952 he chaired four conferences of about 20 conservation and nature organisations that recommended legislation to protect national parks and establishment of a National Parks Authority.

The conference also decided there should be a new and permanent organisation to continue its work, comprising organisations and individuals interested in the preservation of areas of scenic, historical or scientific interest.

Getting established

At a meeting on 26 November 1952, the Victorian National Parks Association was formally established, and its Council appointed, with Morrison as President. Morrison’s chief ally was J. Ros Garnet. While Morrison was the figurehead and public voice, Garnet was the main driving force and organiser behind the scenes.

The Council consisted of 15 members, with only one woman (Miss M. Wigan), plus 15 Corporate Members (naturalist, bushwalking and bird watching clubs and scientific societies) and about 80 individual members.

The official public launch of VNPA was at a meeting held in the Lower Melbourne Town Hall on 23 July 1953 – so many people came that ‘hundreds’ were turned away.

Frustration

The first three years were intensely frustrating for VNPA as it sought to have legislation passed to put national parks on a proper footing. Morrison and Garnet continued tirelessly to push the cause.

Finally, in October 1956 Henry Bolte’s Liberal government passed the National Parks Act, and in May 1957 the National Parks Authority (NPA) was created, with Morrison as its first director. Morrison resigned as VNPA President to take up the position.

For a brief period, it looked like a great victory, but cracks soon appeared. The NPA proved, despite Morrison’s best efforts, to be weak and flawed in its powers, authority and finances. All this took a toll on Morrison, who tragically died, aged 58, of a cerebral haemorrhage in March 1958.

Morrison’s work was still far from complete, but he will be long remembered and appreciated for what he achieved in a life devoted to the preservation and protection of the environment, and especially our national parks. It is fitting that he has a building named after him at the National Botanic Gardens in Canberra.

The weaknesses of the NPA meant that the battle was renewed, both to protect existing parks and to have new ones created, as well as the broader battle to protect Victoria’s natural heritage.

J. Ros Garnet and scenery preservation

In December 1958, VNPA Council discussed what it saw as necessary amendments to the Victorian National Parks Act.

J. Ros Garnet’s suggestion was to rename the legislation as the National Parks and Scenery Preservation Act. ‘Scenery preservation’ was already a dated concept in 1958. In the 19th and early 20th centuries the reasons behind nature reservations were essentially anthropocentric – to preserve places for human enjoyment (such as the preservation of grand scenes) and for future human scientific research or other benefits.

But by the 1950s, educated and aware environmentalists looked beyond human benefits and were at least equally concerned about the ‘rights of nature’, biodiversity and ecosystem preservation.

So why did Garnet, who seems to have been so acutely aware of such issues, support scenery preservation? The reason appears to be that ‘scenery preservation’ was both a reflection of his love of nature and part of his strategic thinking to protect Victoria’s natural heritage. In various writings Garnet referred to the beauty and joy of scenery as part of what he wanted to preserve.

At the same time, he was aware that there were benefits to be gained by extending the concept of nature protection beyond national park boundaries. To advance ‘scenery preservation’ might enable the consideration of adjacent wider areas.

Ros Garnet (1906-1998) was a most interesting character and one of the most important individuals in the foundation and early years of VNPA. Because Morrison died prematurely, Garnet’s role was longer and more influential. A keen naturalist, with a special interest in indigenous botany (notably orchids), he was particularly interested in Wilsons Promontory and Wyperfeld National Parks, and wrote booklets about their natural and human history.

In 1966 he was awarded the Australian Natural History Medallion and in 1982 was given an Order of Australia (AM) for services to conservation.

Few have done as much for VNPA, Victorian conservation and ‘scenery preservation’ as that most committed activist, Ros Garnet.

Grievances to garden party – the 1960s

The 1960s were a fractious time in the relationship between the environmental movement and the Bolte Government. Early optimism after Bolte had passed the 1956 National Parks Act had turned into disappointment and then anger and distrust, culminating in the Little Desert dispute of 1969-70.

Much of VNPA’s effort in the 1960s was devoted (generally unsuccessfully) to encouraging the government to establish new national parks and to expand existing ones. However, it was also often on the back foot, fighting defensively for gains that it had already won or defending areas that it hoped would become national parks.

In essence, much of the decade was spent putting out the spot fires, many which have continued over succeeding decades. Many of the challenges and events that were faced back then have been repeated since, notably the expectations of the timber industry and mountain cattlemen and the pressures for the commercialisation of national parks.

The Little Desert and Bolte’s departure

Henry Bolte and his ministers, while paying some lip service to ‘conservation’, were essentially supportive of development and growth economics, and gave little support to the environmental movement or the extension of the national park system. Over the decade the relationship between Bolte and VNPA soured.

What brought matters to a head was the 1968 plan to develop for farming most of the Little Desert in western Victoria. VNPA campaigned from the late 1950s to have most of this area declared a national park, especially as it was one of the few areas where the Mallee Fowl was still relatively numerous. Lands Minister Sir William McDonald, who saw the land as wasted and useless if it were not being made productive.

The Little Desert plans coincided with another government proposal to allow pine plantations in the Kentbruck Heath region of south-western Victoria, where VNPA had been seeking declaration of a Lower Glenelg National Park.

Environmental groups united to fight these causes, especially the Little Desert, and formed the Save Our Bushland Action Committee (SOBAC) in which VNPA President Gwynneth Taylor played a major role. SOBAC received strong support from The Age and the wider public.

So strong was this community and political backlash that a change of direction began to emerge in Bolte’s policies and administration, such as the establishment in 1970 of the Land Conservation Council (LCC) to advise on the ‘balanced’ usage of public land, and the creation of the Environment Protection Authority.

When Bolte retired in August 1972 and was replaced by Dick (Sir Rupert) Hamer, a new era commenced. And the new Premier even invited VNPA to a garden party at Government House.

Developments at Mt Buffalo

The only alpine area included in the 1956 Act was the long-standing reservation at Mt Buffalo where the Victorian Railways ran the Chalet. Defending this national park became a constant problem.

The main challenge at Mt Buffalo was over the perceived role of a national park. On the one hand, environmentalists argued that once declared, reservations should be permanent and that human activity needed to be tightly controlled in order to protect natural systems.

But outside the environmental movement there was another view – national parks were sometimes seen as little more than temporary reservations of recreational areas that could and should change and adapt to meet the needs of free enterprise, tourism and community recreation.

In 1960 the government legislated to enable areas within national parks to be leased for commercial purposes. Soon after, plans for a tourist development were announced for Mt Buffalo and in 1964 the Tatra Inn was opened.

VNPA staunchly opposed the leases and the presence of commercial enterprises within national parks, and while it failed initially at Mt Buffalo it took a stronger and ultimately successful stand against similar proposals at Wilsons Promontory.

At Mt Buffalo, however, there was periodic revival over the next eight years of a desire to create a recreational lake near the Inn, and in 1971 to undertake a major expansion of the premises. VNPA fought these all the way, and finally in 1972, after Bolte had retired, the Hamer Government announced that it would not allow any further development. In 1975 the lease was bought back.

Peaks and valleys – the 1970s and 1980s

Over the last 70 years VNPA has struggled up steep climbs to elated successes, interspersed with deep plunges into frustrated disappointments as it has campaigned to protect nature in Victoria.

The years between 1970 and 1990 were particularly mountainous because of the charged political atmosphere and the crucial role played by the LCC. The LCC consisted principally of senior public servants, notably the Forests Commission of Victoria (FCV) which fought bitterly to reserve access of forests for the timber industry.

The main issues in these two decades included advocating national parks in the Alps, Grampians, Otways and East Gippsland, and resisting the woodchipping of old-growth forests.

An alpine national park?

One of VNPA’s major ambitions was the creation of an Alpine National Park, but there were many interest groups opposed to the concept.

Local government bodies feared that national parks would damage the industries upon which their communities depended. Together with the Forests Commission and the timber industry, they opposed national parks that would significantly curtail logging in alpine regions.

Over the years, the Forests Commission built an extensive network of access and firefighting tracks through sensitive alpine areas, much to the horror of the environmental community. Another source of concern, although more in East Gippsland, was the emergence in the late 1960s of the woodchipping industry.

Mountain cattlemen resisted any reduction of their leasing of mountain areas for summer cattle grazing. The Mountain Cattlemen’s Association assured VNPA that cattle did not cause erosion, and that offroad vehicles and trailbikes were a greater problem. In the latter they may have been correct, for as affluence and mobility increased there was major influx of offroad vehicles in the 1960s.

Tourism more broadly, and snow skiing in particular, brought higher visitation and greater exploitation of alpine regions. Areas that VNPA hoped to have included in a national park were developed as ski resorts and tourist attractions, with all the accompanying road and accommodation impacts.

One of VNPA’s principal contributions to the campaign and to public awareness was commissioning Dick Johnson to write The Alps at the Crossroads, an assertive assessment of the various threats to the Alps and the need for a national park. He was assisted by a team of VNPA people including Sandra Bardwell, Geoff Edwards and Ann and Lindsay Crawford. The book was published in 1974, quickly selling 10,000 and eventually 23,000 copies. It had a considerable impact on public knowledge and concern.

The LCC presented its first recommendations on the Alps in mid-1978 but, to the horror of environmentalists, only small areas were recommended for protection and there would be no significant new national parks. This was one of the deepest periods of disappointment.

Regathering their strength, VNPA members prepared their response and threw themselves back into the campaign. The final LCC recommendations in 1979 were a minor improvement, including four small new national parks in the east and Alps: Wonnangatta-Moroka, Bogong, Cobberas-Tingaringy and Snowy River. There was also to be an Avon ‘Wilderness’ and other lesser extensions and creations.

However, grazing, mining and hunting were to continue in many areas, and others were to be logged before they were declared part of a protected area or national park. The latter concession was accepted by VNPA in order to get sufficient political support for the parks.

Premier Hamer accepted virtually all of the LCC recommendations and, in the face of intense lobbying by opponents, in 1981 the legislation establishing these parks was passed.

By then, faith in the Liberals had waned among environmentalists and a resurgent Labor Party had developed a promising environmental policy that included the large contiguous Alpine National Park that the VNPA craved. In 1982 the Labor government of John Cain was elected, and within weeks the new Minister, Evan Walker, directed the LCC to reopen a Special Investigation into the Alps.

Anticipation and success

VNPA spirits rose rapidly and it quickly produced a submission and looked forward with anxious anticipation for the LCC recommendations. When they were published in 1983, they included much of what VNPA wanted, and when the government accepted them there was a peak of elation.

Political reality then set in and there were another six years of political battle before the Alpine National Park was legislated for and declared. The main reasons for the delay were the opposition of the Liberal Party, National Party and Mountain Cattlemen, and Labor’s difficulty in passing legislation through the Legislative Council.

Nevertheless, Minister for Conservation, Forests and Lands Joan Kirner, a keen supporter of the environment and the Alpine NP, used other means to promote the Alps. She undertook a cooperative management arrangement of the Alps with the NSW and ACT governments, and offered support for nominating the Australian Alps for World Heritage status.

Finally, the Liberal Party moderated its stand. Shadow Minister Marie Tehan was able to persuade her party to accept the Alpine Park legislation when it was presented by a new minister, Kay Setches, in 1989. After a long debate, many amendments and much negotiation the bill was passed in May and the Alpine National Park was declared on 2 December 1989.

This was one of the highest peaks reached by VNPA in its history.

The 90s: Keeping what we’d fought for

Political neutrality was very difficult in the 1990s as the Kennett Government was a far cry from the progressive stance on environmental matters of some earlier Liberals. The Kennett neo-liberal faith in small government and market forces, and its utilitarian view of the natural environment, eroded the values that had created the national park system. Government decisions frequently threatened environmental degradation through inappropriate tourist developments, commercialisation and privatisation. In the words of Doug Humann, the Director for most of the decade, the period was ‘tumultuous’ and ‘like stepping through a minefield’.

While much VNPA time, energy and resources were devoted to filling gaps in the national park system, only 127, 864 ha was added in these 7 years, while a significant outlay was required to fight a rear-guard defence of what had been won since the 1950s.

Filling the gaps

Victoria’s Box-Ironbark Woodlands.By the late 20th century about 85 per cent of box-ironbark woodlands had been destroyed and most of the severely degraded remnant was in a few small forest areas. A campaign was led by Charlie Sherwin and Barry Traill and in 1996 the LCC began an assessment. It worked very slowly and its Report was not released before Kennett’s defeat in 1999. It was left to the new Bracks Labor Government in the new century to legislate for protection of box-ironbark areas in 2002.

Central Highlands/Yarra Ranges. Since 1987 the LCC had been assessing this region, but most of its 1993 recommendations for a national park included land already in closed catchments around reservoirs. Led by Anne Casey, VNPA campaigned for a much greater area, but when Yarra Ranges NP was officially opened in December 11995, 80 per cent was made up of water catchments. It was only a quarter of what VNPA recommended and left 465,000 ha available for logging.

Marine, Coastal and Fisheries. Protection and conservation of coastlines and seas had been on the VNPA agenda since the 1970s and they were the ecosystems still least protected in the 1990s. The campaign was mainly led by Nicci Tsernjavski, Kate Brent and Tim Allen. In 1993 the LCC commenced work on an investigation but it became a complicated and drawn-out issue with a great deal of fishing and angling resistance. Here too, the final recommendations of the LCC and its successor, the Environment Conservation Council (ECC), had also not been released before the change of government in 1999.

Grasslands. Only remnants of previously widespread grassland ecological communities were extant across Victoria. VNPA’s grasslands campaign, largely led by James Ross, encountered indifference (because the ecological value of grasslands was seldom recognised) and resistance (because of the value of the land for residential and other purposes). Finally, in 1997, 1277 ha of privately owned grassland at Terrrick Terrick was acquired and added to the 2493 ha state park which in 1999 was declared Terrick Terrick National Park. The campaign was not over.

Defending what had been won

Overwhelmingly, during the Kennett years, VNPA was forced to defend what had been won in previous decades, because of government desire to commercialise and privatise parks and services. There were two issues in particular that were fought by VNPA.

Wilsons Promontory National Park. In November 1996, the government announced plans for the development of a 150-bed three star licenced ‘lodge’ at Tidal River plus other commercial developments. There was an immediate public backlash led by VNPA, with Karen Alexander managing the campaign, working with Doug Humann. Most notable was a gathering of volunteers on the Tidal River beach on 29 December 1996 where some of the 2000 in attendance shaped themselves into the words ‘Hands Off!’, photographed from the air. In the face of public disquiet the government shelved the lodge and some of its ambitions but the potential threat remained, and VNPA maintained its campaigning until the change of government.

The Alps and the Alpine National Park. In 1996 Victoria entered the longest period of drought and high temperatures in its recorded history, which lasted until 2009. There was alarm at the impact on fragile ecosystems, notably alpine regions which were already under the onslaught of clearing, logging, 4WD and bush bikes, cattle grazing and ski resorts. The most dramatic new threats were generated by pressure to expand and service ski resorts, notably a new resort at Mt Stirling, and the excision of land from the Alpine NP to add to the Falls Creek resort.

VNPA fought these and was successful in fending off the Mt Stirling plans but was aghast at the precedent set by the excision of part of a national park. Added to this, in 1998 the government reissued cattle grazing licences in the Alpine NP for another seven years.

A new century and a changing climate 1999 to 2010

A dominant issue from 1997–2009 was that much of eastern Australia was in sustained and profound drought with rainfall in Victoria below the long-term average and temperatures in the top 10 per cent. One result was three of the worst periods of bushfires since colonisation, in January-March 2003, December 2006-February 2007 and February-March 2009. Climate change had arrived, although not everyone in the community was convinced.

Politically it was a more amenable and productive period. In 1999 the Kennett Government was defeated by Labor’s Steve Bracks. Bracks was succeeded by John Brumby, and the Liberals did not return to government until Ted Baillieu won office in December 2010.

Labor fulfilled many of VNPA’s aspirations, thanks substantially to two consultative and determined Ministers: Sherryl Garbutt to 2006 and then John Thwaites to 2007. Some gains/advances were rapid, others slow and watered down largely because the Liberals and Nationals controlled a hostile Legislative Council. Nevertheless, the Bracks/Brumby period added 364,473 ha to Victoria’s parks. As gaps in the parks system were filled, wider environmental challenges drew VNPA into landscape-wide environmental issues.

1999–2002: Three frustrating but successful years

The new government’s first achievement was a National Parks Amendment Bill in June 2000 to return the 285 ha that had been excised at Mt Mackay back into the Alpine NP. Soon after, the government introduced legislation to replace the ECC with the Victorian Environment Assessment Council (VEAC) but met stronger resistance, particularly because the new authority was to be able to consider private land. The opposition parties refused to compromise and the government was forced to concede that VEAC would be limited to Crown land. The legislation was passed in December 2001 and the VEAC Council appointed in July 2002.

Marine Parks. After two decades of agitation by VNPA and 7 years of assessment, in early 2000 the LCC released marine recommendations. There followed nearly three years of campaigning by VNPA (led by Chris Smyth) to combat resistance from fishing and other interest groups and the Opposition. At one point the government withdrew legislation because of the impasse. Finally, on 13 June 2002 bipartisan support passed a Marine Parks Bill. The parks were formally gazetted on 16 November 2002. The achievement was ground-breaking as Victoria was now a world leader in having a network of marine national parks and protected areas. A sobering realisation was that only 5 per cent of relevant waters were yet protected.

Box-Ironbark Parks. The box-ironbark campaign followed a similar trajectory. The long-delayed LCC recommendations in 2000 and 2001 were deeply disappointing, providing for only 6% of this greatly reduced and threatened ecosystem. Only 17 per cent had survived since colonisation and most would still be left open to further exploitation for timber and mining.

A political standoff continued until about ten weeks before November 2002 election, when the government introduced legislation. Under considerable public pressure the Liberal Party supported the legislation which passed in October 2002. It provided for 69,000 ha of national parks, 27,000 ha of state parks, 7,000 ha of national heritage parks and 59,000 ha of nature conservation reserves. This was a very large total, but fell short of the ideal level of protection in many areas. The parks were proclaimed on 20 October 2002.

Battles still to be won

Fiery Climate, the Alps and Cattle Grazing. As the drought worsened, there was increased concern about impacts on Victoria’s natural systems from future climate change including heat stress, reduced rainfall, water shortages and bushfires. Among many areas, the Alpine NP and Grampians/Gariwerd NP were badly burned. Damage to the Alpine NP made it even more important to remove cattle grazing and in the face of trenchant opposition a major campaign led by Phil Ingamells, Charlie Sherwin and Tom Guthrie ensued. Finally, legislation to stop the practice passed through the Legislative Council in June 2005 – after 50 years of campaigning. However, the Liberal and National Parties threatened to return the cattle once re-elected.

Red Gum Forests. The red gum forests and wetlands lining the Murray River and tributaries were unprotected and increasingly stressed by the drought. VNPA conducted a long campaign that saw Nick Roberts, Phil Ingamells and Geoff Lacey work with local groups including, most importantly, the Yorta Yorta traditional owners. In 2005 a VEAC study commenced on the stretch from Yarrawonga to Swan Hill. Its interim report in 2007 was described by VNPA as ‘outstanding’ and ‘visionary’. After much opposition and delay, legislation was passed in November 2009 to protect 100,000 ha of red gum forest including four new national parks: Barmah, Gunbower, Lower Goulburn River and Warby Range-Ovens River. The parks were declared in June 2010.

A small number of new or enlarged parks was established during this decade, including, the Greater Otway NP, Point Nepean NP and Cobboboonee NP. Less successful overall were the campaigns to protect Victorian remnant grasslands, despite the efforts of James Ross and John Sampson. A joint federal-state process called the Melbourne Strategic Assessment resulted in some limited grasslands protections in the Melbourne region.

As gaps were filled, VNPA was determined to respond to the impacts of climate change and mounting recognition of the extent of damage to the environment since European arrival. Victorian ecosystems were under enormous stress, both within and without supposedly protected areas.

Declaration of a park or reserve was not sufficient to ensure its long-term health. There was a need for a landscape-scale approach to protecting and repairing what was left of Victorian ecosystems and VNPA worked on numerous environmental issues. Much effort was focussed on the protection or rehabilitation of ‘remnants’ – small areas of valuable ecosystems, often isolated and vulnerable, on government and private land. For a number of years Karen Alexander ran the Remnants Project to address these issues.

VNPA increasingly worked with other organisations in ‘networks’ (e.g. Victoria Naturally) and recruited large numbers of volunteers for working bees to plant, weed and other rehabilitation activity in such as Project Hindmarsh and Grow West. Monitoring programs such as ReefWatch and NatureWatch were cooperative activities using volunteers.Inevitably, there were spotfires to be put out or small conflagrations to deal with, some of which included: the fruit bats in the Melbourne Botanic Gardens, wind farms, a proposed toxic waste facility near Nowingie and the Hattah-Kulkyne NP, channel deepening in Port Phillip, and a high speed train through eastern Victorian forests.

A full version of the updated VNPA History, by Don Garden, will be published in coming months.

Image: Jerry Galea, Courtesy of The Age

Did you like reading this article? You can read the latest full edition of Park Watch magazine online.

Want to be kept up to date about this and other nature issues in Victoria? Subscribe to our email updates.

You can also receive our print magazine Park Watch four times a year by becoming a member. Find out more.